Guild Companions in North American

The Guild of St George has a growing body of Companions in North America. As well as their own work, research, scholarship and personal interests, the North American Companions work with other like-minded partners to programme events, visits and conferences.

If you would like to find out more about specific activity on the continent, please contact Professor James S. Spates here or Dr Sara Atwood here for further information. In 2020, they led the foundation of the RUSKIN SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA. Anyone interested in the life and work of John Ruskin resident in North America is welcome to apply to join this Society.

James Spates also writes a richly rewarding blog, WHY RUSKIN, full of fascinating thoughts and insight into Ruskin.

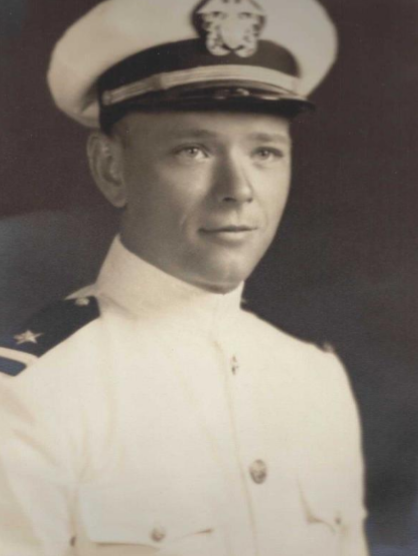

Van Akin Burd (1914-2015)

Professor Jim Spates tribute

Listen to Companion Prof Jim Spates paying his warm tribute to his friend and fellow Ruskin scholar, Companion Van Akin Burd, who sadly died in 2015. You will even be able to hear a clip of Van himself.

With thanks to Mike Salts and the Friends of Ruskin's Brantwood for permission to make this lecture available online.

(NB. In order to listen to the lecture, your browser will take you to a third-party site called Clyp.)

The Guild's 100th birthday tribute

Download the Guild's 100th birthday tribute to Van taken from The Companion Magazine.

Van in the Navy

Jim Spates' obituary of Van Akin

Read Jim Spates' touching obituary of Van Akin Burd

VAN AKIN BURD (1914-2015)

Arkansas Intimacies with John Ruskin

Dr Kay J Walter,

University of Arkansas at Monticello

For two weeks from mid-May 2016, I experienced “the best trip ever,” declared to be so by my students. Four students from rural Arkansas came to Great Britain with me for a travel seminar in British Authors. This upper-level university course afforded my students intimate learning opportunities which traditional classroom lectures cannot. They toured the homes, villages, birthplaces, workspaces, inspirations, and gravesites of many authors they knew from their studies. Not all of the authors’ names we explored were familiar to them, though, and every day the students made new connections and experienced firsthand the organic nature of learning to develop vital networks among their understandings. Daily the students encountered new awarenesses that inspired them to proclaim each day of the journey “the best day EVER,” but called upon to pinpoint a highlight of the trip at the end, they enthusiastically voiced a newfound fondness for John Ruskin and their time spent studying him.

Students who people the classrooms I teach inevitably hear of Ruskin. Somehow his words, ideas, experimentations, or humor find their way into every course I teach. His comments about the flaws inherent in Lady Macbeth from “Of Queen’s Gardens” show up in my Shakespeare course. His views about Pre-Raphaelite art and his environmental concerns color my students’ understanding of Victorianism in World Literature. His comments on the nature of Gothic culture as expressed in their architecture inform my students’ views of medievalism in British Literature I. My drama class learns about the importance of reading “letter by letter” from “Of Kings’ Treasuries” and how focusing carefully on a brief reading selection can result in comprehension. This comprehension enables them to share understanding with an audience through dramatic reenactment of the plays we study. In every case, attention to detail and its ability to yield not merely comprehension but awareness of meaningfulness and utility of understanding form the foundation of my approach to teaching students what to read and how to learn.

Even my freshmen are charged with an assignment to read The King of the Golden River aloud to an audience and reflect on the challenge of presenting Ruskin to a child. The preponderance of my young learners are encountering Ruskin’s name for the first time, have no experience reading literature aloud, and grow up in homes without books. For some of them, this lesson is the beginning of a future of reading as a habit, a preference practiced with care and vigilant patience. I rely upon these students to help me share Ruskin with the world—one story at a time, one child at a time. For some, this fertile start bears fruit in future research projects and the choice of further coursework and fields of study.

Last fall one such student decided to add a major focus in English literature to his course of study in Computer Information Systems. This dual program of courses presents an interesting juxtaposition of fields exploring the overlap between the traditional study of literature and the current focus on electronic and technological advances and virtual information and storage of texts. But even English classrooms weren’t enough to satisfy this young scholar. He wanted an intimate experience with the writers he hoped to learn. In particular, he wanted to experience John Ruskin as directly as possible in the twenty-first century.

My university is very keen on a concept modern terminology labels “service learning.” This is merely a new name for a very old method of learning and an idea Ruskin would recognize and approve. It involves the volunteering of time to actual and personal effort toward advancing the causes of the material studied and eliminating challenges that interfere with its mastery among a group of people in need of extra assistance. Such projects are often undertaken by education students studying to be the schoolteachers of young children. In such cases Service Learning projects may take the form of reading books to classes of Primary school children or helping Secondary school students with homework after classes end for the day or planting flowers near the door of a school for Special Needs students. Other fields of study occasionally take up the cause of Service Learning, but the study of English rarely includes Service Learning in any form.

I am convinced this is a pedagogical mistake. My students benefit greatly from any opportunity to manipulate the material they study. Attention spans are shorter among the current generation, and reading skills less practiced. Information they must acquire solely through decoding text on a page puts them at high risk of failing in mastery. The more important the knowledge they must acquire, the more important my efforts at supporting and enhancing their mastery becomes. If I can invest their efforts to learn with personal relevance, and particularly if the efforts incorporate more than their eyes as a pathway for learning, the likelihood of mastery increases. When they are thinking and moving and working with their eyes and ears and hands and hearts, such likelihood becomes a probability, and this is a concept Ruskin understood instinctively.

I am convinced this is a pedagogical mistake. My students benefit greatly from any opportunity to manipulate the material they study. Attention spans are shorter among the current generation, and reading skills less practiced. Information they must acquire solely through decoding text on a page puts them at high risk of failing in mastery. The more important the knowledge they must acquire, the more important my efforts at supporting and enhancing their mastery becomes. If I can invest their efforts to learn with personal relevance, and particularly if the efforts incorporate more than their eyes as a pathway for learning, the likelihood of mastery increases. When they are thinking and moving and working with their eyes and ears and hands and hearts, such likelihood becomes a probability, and this is a concept Ruskin understood instinctively.

After all, the young Oscar Wilde and Hardwicke Rawnsley in cricket whites building a road through the muddy swamp between Upper and Lower Hinksey is a form of the same emphasis on manual labor my students undertook at Brantwood. It was an experience meant to connect the lads to the needs of the villagers, to dirty their hands with the redemptive toil of manual labor on behalf of those in need and to focus their energy and attention upon work resulting in material and evidentiary good. The fact they were denied the fulfillment of their labor by Ruskin’s abandonment of the project in no way invalidates the pedagogical soundness of the teaching strategy.

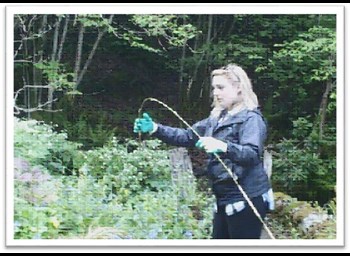

When my student undertook a Service Learning project at Brantwood, it was not so grand an effort as roadbuilding. The scope of our effort was confined by temporal restrictions. On our trip from Arkansas, we had only one day to spend at Ruskin’s home, so the task was devised with our circumstantial confines in mind. In addition, we were in no way able to undertake skilled labor. My students were inexperienced foreigners. However, they were enthusiastic and willing. Ruth and Dave Charles, the Gardening Team at Brantwood, were very kind to take time out to oversee the effort of my learners.

Not all my students were teenagers. Members of the group ranged in age from nineteen to fifty-two, with widely differing levels of health, sedentary habits, familiarity with nature, background knowledge, and ability. Ruskin’s idea of education always begins with health, so putting my young learners out into the grounds of Brantwood seemed a perfect start. Tidying litter from the foreshore initially sounded to them like “make work” meant to occupy their time and hands without importance, but Paul Dawson provided information about the historical significance of the harbor to Ruskin’s ideas for his home and to the ongoing need for its attentive upkeep. We discussed Donald Campbell and the key role Brantwood’s foreshore played in his efforts to claim the world speed record. Dave passed around gloves and explained the prevailing wind patterns and the nature of water flow that results in debris from the lake finding its way to the shores of Brantwood. At this point, my learners were eager to don work clothes and take active part in maintaining a space integral to the history and wonder of Brantwood. Their work day did not end there, though.

Not all my students were teenagers. Members of the group ranged in age from nineteen to fifty-two, with widely differing levels of health, sedentary habits, familiarity with nature, background knowledge, and ability. Ruskin’s idea of education always begins with health, so putting my young learners out into the grounds of Brantwood seemed a perfect start. Tidying litter from the foreshore initially sounded to them like “make work” meant to occupy their time and hands without importance, but Paul Dawson provided information about the historical significance of the harbor to Ruskin’s ideas for his home and to the ongoing need for its attentive upkeep. We discussed Donald Campbell and the key role Brantwood’s foreshore played in his efforts to claim the world speed record. Dave passed around gloves and explained the prevailing wind patterns and the nature of water flow that results in debris from the lake finding its way to the shores of Brantwood. At this point, my learners were eager to don work clothes and take active part in maintaining a space integral to the history and wonder of Brantwood. Their work day did not end there, though.

They were allowed a tea break in the private area of the house and then taken out to the garden to learn about building plant supports from natural materials. Birch bracken and bamboo shoots were shaped into forms to hold the coming blooms upright and tall as budding plants blossomed in the early summer. Correctly assembled, the birch weaves into a stand nearly invisible beneath the bright blooms, showing the garden at its loveliest splendor. The bamboo bends into edging that fades from notice and accentuates the brightness of the plants inside its arches. My students took great pride in weaving well the bracing webs of birch. Afterward, they stood back and admired their handiwork with dirty gloves complemented by joy and pleasure obvious in their smiles.

Just before they flew home, Nicholas Friend took them on a tour of the National Gallery which included lessons in JMW Turner’s painting. When he asked them about highlights of their trip, they declared their day at Brantwood the summit. Their hands-on efforts in Brantwood’s gardens gave their lessons about John Ruskin and his ideas immediacy, and their manual labor gave them a feeling of ownership, a physical contribution to their learning which resulted in an intimacy and a fondness words sometimes fail to produce in isolation.

Just before they flew home, Nicholas Friend took them on a tour of the National Gallery which included lessons in JMW Turner’s painting. When he asked them about highlights of their trip, they declared their day at Brantwood the summit. Their hands-on efforts in Brantwood’s gardens gave their lessons about John Ruskin and his ideas immediacy, and their manual labor gave them a feeling of ownership, a physical contribution to their learning which resulted in an intimacy and a fondness words sometimes fail to produce in isolation.

While I do not expect the Brantwood Gardening Team always to make time for my students’ Service Learning, they were genuinely assisted by our work. I was informed that my students accomplished in an hour what would have taken the Gardening Team a whole morning to do. The success of our endeavor is already inspiring future Service Learning projects. John Iles has offered to find useful work for willing (if untrained) hands that will create a Service Learning project at Uncllys Farm as we learn about the Guild of St George and the Wyre Forest on the next travel adventure. If the summer of 2017 offers another opportunity for students from my university in Arkansas to travel to England, it seems that their entire course might be built around the study of John Ruskin and his Guild of St George!

I suspect Ruskin would very much approve and that all education benefits from a Service Learning element. In the same way that teaching something enhances the understanding of the teacher, Service Learning will enhance the understanding of the learner by providing a context for comprehending its relevance and for recognizing its needfulness. The service my students provided to Brantwood’s ongoing efforts to forward the work of John Ruskin involved their hands as well as their intellects in embracing new ideas. Just as reading aloud provides additional input to assist students in learning their lessons by including the eyes and the ears in the teaching, involving the hands offers tactile sensations that also enhance the material we study.

However far removed my students are from Coniston, however unprepared they are to read Ruskin for themselves, however detached they feel from academic, cultural, and international causes, they are young learners Ruskin in his Christian traditions would insist we champion. “Suffer the little children,” Christ tells his disciples, and the Guild’s interaction with my young scholars in Arkansas is much the same. While they are not all chronologically “children,” intellectually they are very young, can learn, and are eager to undertake the study of Ruskin.