Here you will find a growing number of profiles or interviews with Guild Companions, professional partners, friends or associates. We hope you enjoy finding out a bit more about these remarkable people and their diverse interests and experience.

PROFILES

Ruskin Collection curator Ashley Gallant

Companion Terry Johnson

Companion Déirdre Kelly

Companion Kateri Ewing

Companion Lefteris Heretakis

Interviewees to come include Richard Channing, Julian Perry, Charlie Tebbutt and Dominika Wielgopolan.

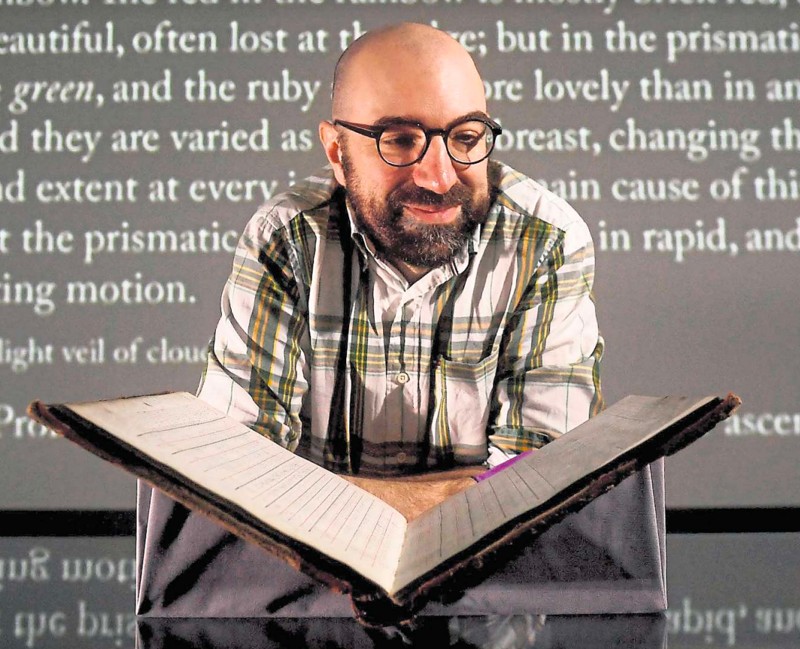

Photograph by Simon Hulme, Yorkshire Post

Ashley Gallant

Ashley Gallant is an artist, educator and curator, and holds the (part-time) post of Curator of the Ruskin Collection at Sheffield Museums Trust. Each year, alongside his many other responsibilities for the collection, he leads on a thematic re-display of the Ruskin Collection gallery. We sat down with him to find out more about his relationship with art, curating and the Guild’s collection, and what being its curator entails.

It was a wide-ranging conversation; Ashley was talking in a personal capacity throughout, and so views expressed in this interview are not necessarily the official views or policies of Sheffield Museums Trust.

Would you like to introduce yourself?

I'm the curator of the Ruskin collection at Sheffield Museums, so I'm based in Sheffield. When I'm not here, I'm a PhD candidate at the University of Nottingham. I've been lecturing in theory of photography, history of art, history of design, and the PhD looks at the role of copyright in museum collections. So I'm arguing in a very Ruskinian way that because public collections are publicly owned, they should be completely free of copyright. I’m challenging how we work and arguing that we've enacted this legal way of thinking, which privileges the artist and we should be privileging the audience.

What does being a curator involve for you?

Before I was the Ruskin curator, I was an exhibitions curator in multiple organisations; I've always worked in museums with collections. So I really see my role as a curator as being a communicator. I'm interested in seeing how things are still relevant today and drawing these lines out from the past. A lot of collections are quite difficult to get one’s head around, so it is about working out which ideas were relevant at the time, why those collections were collected, what ideas were playing out, and then seeing how those ideas are still playing out today. I like to work with people and with the collections and try to draw out these ideas and see why they're still important and relevant today.

And often that's by working with different communities or working with academics or with artists, but always going in relation to the collection and the artists in the collection and seeing how far we can push that. So in the past, I've done things like a big show around Henry Moore and how we collect bones from the land and then commissioned poets to go and walk the land and write poetry. Or working with Christian iconography and mural painting and then working with German artists who were mural painters, who felt the spirituality of spaces. So seeing how far we can leap while remaining relevant.

Is there a difference for you in working with living artists as opposed to working with a collection of work by people who are (mostly) no longer alive? Or is the blend sometimes also what's exciting?

It is sometimes easier working with a collection where the artists are dead. Because you are freer to recontextualise stuff and make new connections. Whereas obviously when you're working with living artists, the connection comes from them. And when commissioning, you don't always know where that's going to go. That is really exciting when working with someone like Billy Hughes, because he came in and saw something completely different in the collection. So it's about finding a different route through.

So I'm imagining then that when working with a living artist, part of the process of curation is choosing the artist and being in dialogue with them. And once they're chosen, you have to let go of something and trust that you've chosen a good person and what they do now is out of your hands?

Yes, it's about facilitating their work and providing the knowledge and the access for them to explore and realise their vision. Whereas when you're curating just with the collection alone, it's more about your vision. But we do that very rarely; we almost always work with charities or communities or academics in some way, so it's very rarely about just ‘my’ vision. That's not how we work anymore.

If we think of the Ruskin collection, when you're thinking of ideas for future redisplays, do you take soundings as to whether your ideas resonate with other people? How does that work?

It works in different ways. Sometimes we work to a theme that's given to us. For the past couple of years we've had ‘Colour' and we've had ‘Craft’ because there were other major exhibitions on those themes happening in the institution. So we could contribute to those exhibitions by loaning works to them, but we also created a show from the Ruskin collection which relates to that theme. So, if I have a theme to start with, I'll go reading and looking in the collection for things that might have that theme in them, and then from that I can jump off and see if there's contemporary things happening that would also resonate.

I've just started working on a show for two years time, which is far more an idea led by me, rooted in the collection. So I’ve had a meeting with the other exhibition and collection curators, to sound them out and see if they thought it was a good idea or if maybe there were too many ideas, which is often the case! And then from that starting point, I might then go out and start to work with groups around the idea; I've come from an exhibition-making background and so my instinct is to make exhibitions from the Collection that help people relate to it, in this case joining the modern and the Victorian.

In that dialogue, where, if at all, does Mr. Ruskin sit?

Well, in a sense, his part is over, he's not here to give any more, and so we are free to work as we choose with what he gave. But because we change the space every year, it's fluid. Sometimes it will directly relate to his ideas and other times I see the collection as something he gave to inspire the people of Sheffield, and so we can use it like any other collection. So, you also have the Graves collection here, or the Usher Gallery in Lincoln, each given by a single philanthropist, but you're not obligated to only represent the views of that one donor. For one thing, the Ruskin Collection has 1,600 artists represented in it, who have their own lives and art histories.

Saying that, I do feel that the main idea is always kind of driven from Ruskin in some way. So the idea I have got to at the moment is around the idea of pattern or ornament or fragmentation, which obviously comes from Ruskin’s interest in stone work, but also from the Owen Jones works that are in the collection. So it's very much coming from one artist but through the lens of Ruskin. Looking at detail is a very Ruskinian idea.

And the next show, in 2026, is about the Storm Cloud?

Yes, so that is very much in reference to the lecture and we are working with a performance maker around that lecture and thinking about quotes from the lecture and how that plays out in the collection, so it is very tightly focused around his writing. Where the following year, it might in contrast be very broad looking.

You’ve talked about the aspects of your work that a gallery visitor will see. Beyond the research and display and all the complexities of that, what do you consider to be your next most important responsibilities?

It’s about caring for the collection, to museum standards. A lot of that is about the admin of recording where it is, checking on it, making sure it's in the right temperature, the right environment, all of that kind of basic stuff. If it's not cared for properly, then it won’t survive and you can't find the stuff that's in it.

Then the next thing is allowing access. As much as possible, with limited time and resources, we allow access to the collection, we share images, we share research. For example, I'll have someone coming in today from a history group who just wants to see something.

So there is doing that kind of work, and then the other enormous job is the cataloguing of the collection. Like a lot of the collections, historically it hasn't been much photographed but now the way that we work as curators is far more digital. If something's not photographed and on the database, it most likely won't get used, because we just don't have the capacity to look through 16,000 things to work out what's there. And, especially in this collection, you might have 150 things just called ‘Venice drawing’, which really doesn't tell you what it is like! So a big thing I've been doing recently is photographing and cataloguing more of the collection.

Which in turn expands your palate of usable things, is what you're saying.

Yes. For the Storm Cloud show, I photographed 1,600 objects and some of them will be going into the display, but literally if that photography and cataloguing wasn't done I wouldn't have the images of them to work with young people to choose the new works. So that's the sort of foundational necessity upon which everything else depends.

Going back to your PhD and the question of imagery and copyright, presumably one possible extension of your increasing digitalisation of the collection is the potential for the democratization of access to that high-res imagery. Ruskin’s gift of the collection could be extended in the digital age by making all the images freely available. Is that something you would aspire to in an ideal world?

It throws up philosophical, practical and financial issues, but yes, in an ideal world, my argument would be that every museum collection would be completely in the public domain and all these images would be useable by anyone. In many large institutions I have researched as part of the PhD, the money bought in from copyrights is a tiny amount of their overall budgets and it costs money to fund the staff to administer the guarding of copyright. I wonder what is being stopped by applying fees to use images, whereas you could just release it and say do what you like with it. It would also be far easier with something like the Ruskin collection because most of it is out of copyright.

I remember years ago this argument being made by the head of digitisation at the Getty, but he said that the push back was always along the lines of ‘But we can’t have Van Gosh’s Irises appearing on cheap tea towels’, which he felt would actually do the Getty, and its collections, no harm at all.

My argument is, well, we can still make those tea towels and sell them if we want, but if we believe this is a public collection, I don't think we can stop others from doing that. So I would argue that you can have special environments which are exempted from copyright. So for example, most archives can make certain forms of copy and they have an exemption because they're an archive. My argument to government would be that museums are also a special environment because they are part of the nation’s public collection. Once something enters the collection, it should lose its copyright; that would be the way of doing it. But I acknowledge that it would be quite a big policy change.

As well as being a curator, you are an artist yourself. What do other living artists think about this idea?

The ones I've asked don't seem to mind it. The theory would be that you would still be paid for your work to go into the museum. A big thing around the policing of a copy is that the law believes that a copy is a copy in any format. So they argue that a drawing is a copy of a painting or a photograph is a copy of a painting. But I think if you're a painter, you don't really believe that a photograph of your painting is a copy. So they don't really have the same worry about people taking photographs of their paintings; they would mind people forging their work. And obviously museums have structures in place to stop that happening.

And of course Ruskin is busy commissioning copies, isn't he? Here is a copy, in the Collection and then you start protecting that copy, which has a certain irony to it.

Exactly. As Ruskin knew, one of the ways in which you learn is from copying. You might think that with the speed and quality of digital media, copying would be encouraged more but it's actually being shut down often.

Changing tack, what is one thing about your work or your profession that might most surprise somebody who doesn't know your world?

I think maybe the kind of vastness of what we don't know. Once you have the word curator attached to you, people think you're the expert. Whereas actually, there are things in the collection that I've never handled or seen and there are artists in the collection that I've never heard of. It’s often not until you get a question or works get displayed that you do that research. So I discover and learn stuff every day. People think you are the expert before you get the job, but really that is just the beginning, and there is an endless sea of things to learn.

And if there was one thing about what you do that you would really like everyone to understand, or just to create a better understanding of how museums and galleries work, what would that be?

I suppose that I think it's really important that we keep things from the past, because they prove things about society. And it doesn't matter if they sit unused or just being cared for for a number of years because at some point they will come back into relevance. I think this comes from one of my first jobs which was working on in Holocaust studies. There is a big idea in Holocaust studies that if you destroy the evidence of a past of a people, then you can't prove their history or existence or learn from that now. I think that's the basic argument for every collection; if it's not there, you can't learn about the past and it can't inform the future. Things come in and out of relevance as times change and that’s why it's so important to have all this stuff. And indeed that it's not for any one age to make a judgement about what it is that should be kept from the past.

And if we are keeping things, we must protect them as well. These things do deteriorate; if they are out on permanent display, they will fade. And if they're not kept in the right environments, they will deteriorate. People sometimes imply that we're hiding stuff, which just isn't true. The Collection is not being hoarded in a room to deprive the public; it is deliberately stored in a very specific room so that it survives for the long term. I've got a guy coming in today to see the Turner watercolour, because it's sleeping (i.e. being kept from light and display) at the moment, but it's sleeping because we know it's been out so long, and we don't want it to fade for future generations. So it's a kind of active keeping of the Collection rather than it just sitting there passively.

So the act of choosing to keep and care for something, even if it doesn't get actively used in any given moment, is an important part of curatorship?

Yes. And there are instances where people collect and keep against the grain of what is seen as normal. Holocaust museums are a really good example because so much of the stuff they keep is horrible, evidence of the most traumatic events, but it's really important to have. And then there's also a museum in America called the Jim Crow Museum. And this couple collected racist memorabilia that a lot of other people were destroying at the time because it's so horrible and offensive, and they now use its awfulness to teach about race relations and histories of racism. If they hadn't had the foresight to say, this is awful but it also says something about American culture and keep it, then that evidence wouldn't be there to use and educate with when worrying stuff happens today. But with this material evidence, you can say no, we've been here before. Because when you look back, when someone's not alive to remember it, what is the evidence and how can you see and understand it?

Did you know that art would be your life from a young age?

I was always interested in objects, collections and artistic expression. Before I'd even graduated I had a studio space in a gallery with my friends and we were showing other young artists. In a rather cringe-worthy BBC News programme when I was about 20, we were asked why we had set up the gallery and where did we see ourselves in five years? And everyone else says they imagine themselves being an artist, but I say, I'm going to work in a museum. I think looking back on it, I'd always been obsessed and passionate about art and I wanted to start showing other people's work. As soon as I started doing that in artist-run spaces, I felt like the audience were just our friends. So it's always been about sharing the passion that I have, and the thing I really enjoy about my job now is talking to people in the gallery, giving tours and seeing people come in and leave with a new idea or a new knowledge or a new take on something. I don't think it’s my job to make people love things, it's just to make people think about them.

So it's an act of communion, of helping make a bridge between the artists, the displays and the viewer?

Yes, I want to take the audience on a journey from appreciating the objects, whether they think them beautiful or otherwise, to appreciating what they might mean in a wider context, which also feeds into the teaching I've been doing. I teach the theory of photography, so the theories of what photos mean in the world, and how photography has changed the world. So much of what Ruskin commissioned, not just his daguerreotypes, has always seemed to me to be what we would now automatically go to photography for, which is the impulse to record things. In the case of Venice, it must be evidenced to support his concerns about the state it was in.

Historically, it's been more about the curator dictating the interpretation and putting across that passion, but now much more it's about us working with other people, so that there are multiple voices putting across multiple meanings and interpretations. I think this is really exciting, because often by working with those groups they introduce ideas that you haven't seen in the work and everyone has a kind of input, their own point of access when they come into the gallery. In those circumstances, the hierarchies of knowledge shift, and we have multiple viewpoints and multiple perspectives, multiple stories that might be told.

What you've just described feels like you are in a sense a convener; you put an object, a display, in front of people who might not otherwise have encountered it and then in a sense it’s ‘OK, over to you guys.’ You’re giving permission for them to have their own response.

It’s quite post-modern the whole thing, isn't it? It's about people having their own approaches, and allowing people to have their own voice in the gallery, and breaking down that hierarchy a bit. Let’s take the example of those drawings of birds we have; you can discuss in an ornithological way, or through the artists and through Elizabeth Gould being one of the first female artists who signed her work; you can discuss them as scientific drawings, you can think about them as examples of print making, but we've also had volunteers interpret them by telling you where you can go out into Sheffield and see the birds. All these perspectives are valid, they're all giving you information about the work and they're all enhancing it.

Naturally, I think in terms of what Ruskin wanted, which was to encourage people to go out from the city centre into the peaks and see nature. So if Ruskin would rather the art led you to nature that the nature led you to art, then in fact the volunteer information, telling you where to find the birds in nature, is more important than what I can tell you about print making.

What is the positive impact you hope your work might have on the world?

That’s a difficult question. If someone comes in and has an experience where they see beauty or joy or think about something in a new way or has an idea they haven't had before or any of that then I think I've done my job. I think there's a lot of hubris when we talk about changing the world, actually. There's a lot going on in the world at the moment, which is really difficult to deal with, and if someone can come and just have a couple of minutes removed from that and look at something beautiful and learn something that's important, then I think that's quite a powerful thing to do. And if that helps them go out into the world and look at a flower they've seen in a different way, then that's really great; I think there is solace in that.

Who are the other people, places or organisations doing things that inspire you?

It sounds biased because I'm a Norfolk boy and they're both in Norfolk. One is called Original Projects https://originalprojects.co.uk/ and it's an artist-run space and they show contemporary art. They took over empty space in a shopping mall in Great Yarmouth. I don’t much like the phrase ‘hard to reach’ communities, but I've been in that gallery and they're opposite the toilets and blokes wander in while waiting for their kids in the toilets, who've never been into a gallery in their lives and they engage with what's going on, because of where they are, and the kinds of work they do. So for instance, there's a big model village in Great Yarmouth and they did a show called What is Model?, and when I was there they had Ryan Gander models next to the local boat club, and then they commissioned sculptures for the model village. It was completely place-based work, and as a result everyone understood what was going on.

And the other one I think of is Jago Cooper at the Sainsbury Centre, https://sainsburycentre.ac.uk/ because as their Director since 2021, he's come into a world art collection as an archeologist, and archeologists have a completely different approach to objects. He's hung a Giacometti from the ceiling, which you can lie beneath, and you can hug the Henry Moore sculptures, and so on. I grew up in Norwich and this was the local gallery that my parents would take me to on a Saturday. There was a show there recently focused on drug taking in ayahuasca ceremonies, and in it were objects I'd known for 30 years, for example some South American bowls. The exhibition showed us that of course these aren't just decorative bowls, these are actually vessels for ritual drug taking, and they’d also worked with contemporary artists around psychedelics. So I think he's doing really interesting, brave stuff that you wouldn't necessarily imagine of a well-funded world history collection.

Finally, here we are a quarter of the way through the twenty-first century, and 150 years since Ruskin and the Swans opened the St George’s Museum in Walkley; what do you think remains important about the idea of a Guild and its collection?

I think the challenge is how to share and use the Collection. Historically, you could have moved it out into different environments and handled it all, and put it on different walls, but now for conservation reasons it very much has to be building-based and looked after to recognised standards. So it's working out how you share it within those confines.

Having it publicly accessible and free here in the Millennium Gallery is really important. We have a lot of things here which you can't see anywhere else, and I suppose in my mind it's not that different to Ruskin’s idea of it being next to the land, and easily accessible, because we're in the middle of town and it's on a popular cut-through and that means we have access to lots of audiences who might not usually go to a museum. We know that Ruskin was attracted to establish a museum here because of the skills of its metal workers; today, far fewer such skills exist and there are far more jobs in the education, health and service economies. So how can the Collection be of service to them?

I think the stuff Tom Payne is doing, touring his interpretation of the Storm Cloud lectures, using the images digitally and getting engagement from different audiences is also important. Sometimes these projects will involve Guild Companions, sometimes they involve others; often we go to them for research or other help.

With the Guild itself, and its Collection, I see it as a kind of socialist approach similar to the NHS where we all pay for the NHS even if we don't personally use it; people who can afford to pay into the Guild do it on the basis that it helps to provide something free for the good of everyone in Sheffield. Museums are really trusted in society as institutions and we have more than 95,000 people coming through the galleries a year.

And in the same way that your land holding can address environmental issues, so we can in the gallery; we covered flooding issues in Sheffield and Venice two years ago, and now the Storm Cloud display will address the way in which our weather is changing.

Ashley Gallant in conversation with Simon Seligman, Summer 2025.

Terry Johnson

Companion Terry Johnson is an architect and calligrapher, and has for many years provided beautiful work for the Guild, which includes writing people's names next to their signatures in the Companion Roll, and the design of the new certificates given to Life Companions.

Terry, tell us about your Ruskinian life.

In the little Georgian market town of Louth, Lincolnshire is where it all really began, but even before that - as a pupil at Clee Grammar School in Cleethorpes - I had been cursorily introduced to Calligraphy as part of the O-level GCE art course. I’d always had a neat hand at school and it just clicked with me.

The art master allowed us to use his own personal art library, where I came across a fairly rudimentary History of Architecture and I recall being quite enthralled with the classical “Orders” of Architecture; each with their historical progression and their meaningful systems of proportion and I could go through a “naming of parts” from the stylobate, column structure, entablature to pediment ( from ground upwards).

And so were born the two loves of my life (as well as my wife, I hasten to add).

Some years later, I started working in an architectural practice in Louth, as I simultaneously pursued my architectural career via a course of external study through the RIBA (though not an easy route). Some of the first exercises required on the course were free-hand sketches and my drawing of St. James church in Louth was one of the first I submitted, together with a pen drawing of one of the apostles carved into the pulpit. The history of the church in verse form came later and was calligraphed to accompany the drawing.

In fact, a close friend who had ended his captaincy of a local golf club, asked me to put the two together as a thank-you gift to the club’s steward. The steward then went on to open a high-class restaurant in the former public library building of Louth and took his gift with him. Not being able to disturb the interior walls of the Grade 11* Listed Building, my piece now hangs above a magnificent “throne” - the first time I have ever exhibited in a Gents. toilet (if you know what I mean) - and so, to a limited audience.

Some years later - and having given up the day job to do so, I obtained my Diploma at Leeds School of Architecture with a Credit in Design Technology for my final year design project which linked to my roots with a proposed design for “New Civic assembly Rooms for Cleethorpes” - sited along the sea front. Much later the local library expressed interest in having my drawings for this and I have since passed them on. What they will do with them, I don’t know. I retained just one drawing - a night-time rendering of the whole promenade elevation.

In the early days of my career, I was classed as an architectural assistant. It is said that an architect’s drawings are a means to an end and so they are but at that time, I vowed to produce the best drawings that I could. I did so and gained a good reputation for it. Of course, those were pre-CAD days, so all drawing and annotation was done by hand. I never did go down the computer route, continuing with my hand drawing, consolidating my reputation and obtaining commissions because of that. I just enjoyed the whole process and still do.

Even after retirement, the drawing continues, frequently and prominently featuring architecture and/or lettering; often both together and all under the umbrella of my “ARTchitecture”. I am also a keen supporter of the world-wide “Urban Sketchers” fraternity. I have found drawing to be an immensely enjoyable pastime (and it can be profitable too).

Though I retired from architectural practise over a decade ago, my interest continues via an involvement with the running of a local u3a Architecture Appreciation group and I have given talks to this group (and others) with “Lettering on Buildings”, “The Classical Orders of Architecture” and “The de la Warr Pavilion, Bexhill”.

The “Lettering on Buildings” interest has included some short magazine articles with one currently underway outlining the origins of our motorway signage - “From Manuscript to Motorway”.

A drawing of Lincoln Cathedral’s west face came about many years later, via a visit to some friends and a trip to Lincoln with a walk around the castle ramparts. This too was nostalgic as I had attended Lincoln Art School to facilitate my architectural studies, during which time I made many sketches in the location as well as preparing some measured drawings of the façade of the cathedral library designed by Christopher Wren and a bay of the cathedral cloisters (all as part of the RIBA study requirements).

Accompanying my cathedral drawing are the words of a song, “The Angels of Lincoln”, penned by John Conolly, a founder member of the original Grimsby Folk Song Club, who willingly gave his permission to use them. His words have a genuine and moving affinity with the architecture. I have often thought that had I not become an architect, I might well have been a stone mason (but maybe not a Jude the Obscure) and thus had a different life altogether.

My right hand has had its Andy Warhol “15 Minutes of Fame’ when many years ago, I played a small part in a BBC Scotland production on “The Scottish Enlightenment”. I am able to write with a quill and this opportunity arose through a friend. I had to play the right hand of David Hume, writing with a quill. It was filmed in two very interesting locations in Edinburgh, one being the HQ of the Scottish National Trust, then in Charlotte Square. When required, my right hand was adorned with a lace cuff, over which I donned the greatcoat as worn by the actor playing the part of David Hume. All a great experience (nervous and very hot when seated in front of a candelabra with lighted candles).

Some years ago, I was asked to write a completely new Book of Remembrance to commemorate the Old Boys of a school in Cumbria who had died in the two world wars. In fact it included six names from the last Boer war - one a V.C. A total of 660 names and 5 have since been added which came to light, even after the preliminary rigorous research. At its completion it was dedicated in the school chapel during a Remembrance Sunday service. I have recently been invited to prepare more work for the school involving some art work.

There is a school of thought that Calligraphic lettering should stand on its own - a very noble sentiment and quite true but I have always liked to include art alongside and within my own work, and so my calligraphy and drawing continue with works for my own pleasure and for many other varied commissions, a number of which have come about via the wonderful area in which I have lived for more than five decades and which was, of course, also the home of John Ruskin.

John Ruskin is oft quoted about many subjects and he had this to say “of the virtues of architecture”; “ In the main, we require from buildings as from men, two kinds of goodness; the first, the doing their practical duty well: then that they be graceful and pleasing in doing it. We have thus altogether, three great branches of architectural virtue, and we require of any building -

- i) That it act well, and do the things it was intended to do in the best way iii) That it speak well, and say the things it was intended to say in the best words iii) That it looks well, and please us by its presence, whatever it has to do or say. But you could apply these principles to very many other disciplines and subjects.

“…all letters are frightful things…to be endured only upon occasion, that is to say, where the sense of inscription is of more importance than external ornament”. Also from J R but you don’t HAVE to agree with him.

BUT I will agree with him when he says “Quality is never an accident, it is always the result of intelligent effort”. - and maybe that little bit more.

I’m sure many Companions can identify with that in whatever they do.

I am always at my drawing board (as my family will tell you) and ready to spread the “word” - either written or vocal - all to “make thoughts visible”. A current work-in-progress is a long, panoramic pencil and water colour drawing of the Oxford cityscape from South Park and which will contain some of Matthew Arnold’s words, from two of his poems about the city and its “dreaming spires”, written and finished in gold leaf - - -

and so it continues.

A is for Art

A is for Architecture

Terry Johnson, ARTchitecture and Fellow of the Calligraphy and Lettering Arts Society NULLA DIES SINE LINEA.

Déirdre Kelly

Would you like to introduce yourself?

My name is DÉIRDRE KELLY and I was born in London UK to Irish parents,

Where are you geographically as you respond to these questions?

In Venice Italy where I've been living for the last 21 Years.

How would you choose to describe yourself professionally?

I am a visual artist. Over the years I have curated exhibitions, worked as an art consultant and guest visiting lecturer at many universities in the UK.

What does your work entail?

I am drawn to the intrinsic beauty of the map as a primary source of inspiration. An ongoing dialogue of observations, annotations interventions, conversations with the aesthetic language of cartography to create personal maps which follow in the tradition of hand-drawn maps and atlases of the past. The work centres around the map of Venice, generating a combination of mixed-media images, collage and artists’ books that re-purpose data from various found sources in order to construct new visual and metaphorical narratives.

What does that involve day to day?

Living in Venice is a dream come true for me. Here from my studio window, watching the daily tides rise and fall, is a reminder that there is only one real boundary, that between water and land. Physically walking the ‘calle’ and bridges of Venice, a daily practice of psychogeography, offers the privilege of ever renewed observations and a sharpened vision of arches, shadows and reflections of the city oscillating between land and water, a vision which links directly to John Ruskin, Walter Sickert, John Piper, Joe Tilson and the many other artists' views of Venice. Tracing and re-tracing, traversing both the 'real' and geographical map, is all part of the process: 'Becoming Venetian'.

What do you consider to have been the essential parts of your education and training to be doing this work now?

I studied art and pedagogy, graduating from Wimbledon School of Art, London with a Master of Arts in Printmaking. Focus on traditional print methods, cultivated an affinity with paper and the book form, in particular artists' publications. Exhibiting work regularly since 1985, I have artwork in many public and private collections including the Luciano Benetton Collection, Italy, Ballinglen Arts Foundation, Ireland, Museu da Gravura, Curitiba, Brazil, National Gallery of Canada Library, M.O.M.A. Library, New York, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford and Tate Gallery Library, London. For a time I was member of the Royal Society of Painter Printmakers. From 1986-2003 founding director and curator of the Hardware Gallery, London, which specialised in exhibitions of printmaking and artists’ books. Hardware was at the centre of the artists’ book revival of the late 1980s and 1990s; now the artists’ books collection is in the British Library and documentation on Hardware Gallery activities part of Tate Archive at the Tate Gallery, London.

What is one surprising or intriguing thing about your work and/or your workplace, that other people might not expect?

My studio has an amazing view looking out onto the water at rio San Marcuola towards Canal Grande. I am privileged to be the permanent guest artist in residence at the Scuola Internationale di Grafica, ('Scuola' in the sense of Venetian Guilds). It is a unique location in Venice, a traditional printmaking studio set up in 1969 by artist Matilde Dolcetti, primarily to host artists visiting from all round the world. I like to think of Italo Calvino's writing on Venice, that when on the 'insulae' one feels confined to a limited portion of the world, but opening the door onto the water, connects directly to a borderless dimension.

Why do you do it?

I have been fascinated by maps for as long as I can remember, working with maps and the universal languages that they speak, is my way of getting to know and understand the world. The mechanisms and language key to reading maps provide a kind of ‘grounding’, a ‘grip’ on the world, a fundamental connection with people, place and time. I believe that there is a human need and desire for physical maps, now more than ever. One of my earliest memories is that of tracing coastlines with my finger wondering how a line could delineate an element like water which is in constant movement and flux. Living in Venice, a city forever poised at the edge of its limits, one feels the relative closeness of that reality and fiction. Reading the cartography requires a leap of faith to bridge that distance, and that’s where the 'wonder' comes in.

What is the positive impact you hope your work will have?

Looking at maps and reading lace. In my 'Tracery' there is a desire to embrace and participate in the rich creativity of the female hand, superimposing new techniques on traditional crafts to give a contemporary reading, so that objects of beauty and adornment can find a new audience and be carried into the future. The hand is our first map of orientation; location is the element that unites maps throughout history. In spite of the proliferation of data and new interaction technologies that make maps all the richer, more dynamic and immersive, it is still necessary to engage with the physical world in material ways. My hope is to heighten awareness and sensibility of the nature of mapping: observing and reading physical maps. It’s always a personal territory as looking at the map takes us back to a world of possible images that we already own, to reveal that we each hold the geography of our destiny within.

What do you value most about what you do?

I've come to value the great privilege that living in Venice allows me, to have direct experience of artefacts key to the history of cartography, the history of print and the origins of the book form.

If you could communicate one essential thing about your area of expertise to people who don't know about it, what would that be?

Every map tells a story, as behind every map there is a person and behind every person is a map.

Who are the other people, places, organisations that you think are doing good work in your field?

The Ballinglen Visual Arts Foundation, based in the West of Ireland, was formed in 1992 to create an environment which allows artists the time and space needed to make work away from other distractions. My first experience there in 2012 was fundamental and I have been returning regularly as a fellow ever since. https://www.ballinglenartsfoundation.org/

Is there a particular place in nature, a sight, a building, a book, a work of art, an experience, that you’d like to encourage Companions and others who care about the world, to experience for themselves?

My experience at Brantwood was magical, I would recommend a visit to the gardens and in particular to the Ruskin pond. First mentioned by Ruskin in 1874, it was carefully designed to gather water from the hill, a 'mirror' for the sky above, "guiding the eye off the land into the reflection." https://www.brantwood.org.uk/

I am often surprised to discover Ruskin's influences in unexpected places. The Museum Building, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland (1857) resembles a Venetian palace, the exterior showing influence of Gothic architecture, columns, capitals and details of natural forms carved by the O'Shea brothers who worked with Ruskin in Oxford and the marble entrance hall is built with stone brought from different areas of Ireland. https://www.visittrinity.ie/blog/trinitys-historic-museum-building/

What do you think art, craft, design and rural and environmental education can be used to make the world a better place?

Ruskin recorded word and image with his own hand seeking everywhere a virtue in the act of creation, without which he argued there can be no true beauty. He placed immense value on the work of the hand, finding in it the workings of the engaged and valued soul. By putting his own hand to design he sought to explain how the artist felt and thought in achieving a work of art. I was inspired to find that he was drawing maps from memory at a young age. Recently I participated in a poster campaign around Venice for 'Ocean's Day', with a hand drawn vertical world map which sought to highlight problems associated with damage caused by cruise ships round the world; the power of the visual image to communicate ideas can never be underestimated.

What concerns you most about the world right now?

Ongoing military conflicts and the ineffectual political response, intolerant of the needs of people in respect to global environmental issues. In this sense the map can be a powerful key, whether thinking about our own individual map or territorial boundaries, cartographies of confinement or of freedom. All maps contain some human bias, feelings, beliefs whether irrational or truthful; the map of the future is in our hands.

What does being a Guild Companion mean to you?

In companionship I have found, mutual support and understanding for the development of my work, experienced first hand when I was invited to make an exhibition for Brantwood, Ruskin’s Lakeland home. The exhibition entitled 'TRACERY, Venice and the Lakes Interlaced', (April-July 2023), explored how Ruskin was inspired by cloth and used the language of lace to convey wider messages. Ruskin-inspired cut paper map works alluded to the perfection of intertwined threads and the rich creativity of the female hand, to reveal new ways of looking at lace, as metaphor for strength and fragility, resonating with the nineteenth century revival of Lakeland Linen and Ruskin Lace.

How would you describe the value or purpose of being a Companion to someone considering joining the Guild?

Being a companion of the Guild means trying to further understanding of Ruskin’s writings and the value that they have in the today's world. It is in being enriched by Ruskin's words and teaching by observation, that one finds resonance, relevance and contemporary reference.

What would you like to see the Guild and its Companions doing in the future?

Continue to take advantage of the digital communications to be open to members globally.

If you had the time and space, what might you offer other Companions to enrich our common understanding and connections?

I am always happy to welcome visitors to the studio, to talk about work and deepen understanding of what it means to live in Venice today. The Scuola Internazionale di Grafica, Venezia is a location for contemporary printmaking, which shares links to the historical context and development of printing and publishing in Venice.

Is there a particular line, or work, or idea, or artistic work of Ruskin’s that resonates for you?

In particular, words from Ruskin's diary when tracing the connections between nature and art in Venice. In a recent small publication of mine 'Tracing Ruskin’s Steps : Landward View from Venice' the quoted Ruskin text writes of the ‘landward view from Venice’ when on a clear day the mountains are visible on the skyline. A reminder of the historical links between the mountains and valleys of the hinterland and the watery city. Walking the passages of Venice, as observed by Ruskin in his diaries, now has a heightened significance of an invisible but still perceivable presence.

Landward view from Venice, Sunday December 30,

Close beside me, the green clear sea water lay quietly among the muddy shingles of the level shore, so calm that it made a little islet at the edge of it, of every stone: as clear as a mountain stream and with here and there a large block of marble, marking the outmost foundations of Venice.

(Notebook M: Diary of John Ruskin, 1849)

https://www.deirdrekellyartist.com/tracing-ruskins-steps-landward-view-from-venice/

Kateri Ewing

Tell us who you are.

I’m Kateri Ewing and I am a writer, artist, and teacher whose work gently invites others to slow down, pay attention, and honour the quiet beauty of their inner and outer lives. Over 25,000 students have taken my courses through platforms such as The Great Courses, Craftsy (formerly BluPrint/NBC Universal), and my own online school, Art & Spirit Studio, where I am known for my thoughtful, accessible approach to creativity.

I am the author of three well-loved books—Watercolor Is for Everyone; Drawing Is for Everyone; and Look Closer, Draw Better—all published by Quarto. Each title invites readers into a more mindful, heart-centered creative practice, and they continue to be widely shared for their meditative tone and welcoming spirit.

I live with my partner Rick and two cats in Western New York. I am a mother of two and grandmother of five. My daughter, son-in-law and their two daughters live near by and my son, daughter-in-law and their three sons live in Ireland. I visit them at least once a year and often wish we could all live there. It’s very hard to come home. I’ve wanted to live in either England or Ireland for my entire life.

How would you describe yourself professionally?

I would say that I am a writer and artist devoted to the practice of seeing, an inheritance I gratefully acknowledge in the lineage of John Ruskin. Through my teaching, writing, and art, I invite others to notice the shimmer of light in ordinary things and to discover the companionship of creativity in their own lives. I am currently at work on Two Stones, a book of reflections and creative practices on carrying both grief and wonder at the same time. My work is an offering of reciprocity: to give back more beauty, tenderness, and attention than I take from the world.

What does your work involve day to day?

On a day-to-day level, my work is a weaving together of writing, drawing, and teaching. Most mornings begin quietly at my desk with words—working on my book Two Stones, shaping essays, or writing for my Substack, fleeting, breathing, human things. Later, I turn to my art, often in graphite or charcoal, where the slow, meditative mark-making becomes both personal practice and preparation for exhibitions. I also create watercolor lessons and projects for my online community, filming and writing in ways that invite others into their own creative practice. Alongside this, I tend to the ongoing work of stewarding my courses, Patreon, and book projects, keeping them aligned with my values of reciprocity, presence, and noticing the beauty of the ordinary. I have a part-time job as a fine art framer, which is probably the most difficult thing I do! It involves a lot of math and precision and physical work and it’s about nine hours on my feet. I am really tired when I get home, but it helps keep the lights on, for sure.

What do you consider to have been the essential parts of your education and training to be doing this work now?

I actually began at university studying classical archaeology and languages, and I once imagined I might become a curator in a natural history museum. After a personal tragedy in my final year, I never went back to finish my degree. Motherhood soon stole my heart, though, and I chose to stay home with my children, never really entering the workforce until I was suddenly divorced at 43. At the same time, I faced a decade of serious health issues and surgeries, which left me with a lot of down time in between my working hours at a minimum wage job. I decided to teach myself how to draw in the early mornings and then again after work, and in the process I discovered John Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing. From there, everything unfolded: years of hard work, taking risks, and, I think, a healthy measure of good fortune. Looking back, it feels like a meandering but marvellous path that shaped me far more deeply than any single straight line of education could have. Honestly, I am still amazed at how my career unfolded, and I am really proud of what I have accomplished, especially considering all of the health struggles I have endured.

What is one surprising or intriguing thing about your work, that other people might not expect?

One thing people might not expect is that one of my studios is in the historic Roycroft Print Shop in East Aurora, New York. The floorboards creak with every step, and I often think about the generations of craftspeople who worked there before me. That sense of lineage—of Ruskin, William Morris, and Elbert Hubbard—infuses my daily practice with humility and gratitude. It feels less like I work in a studio and more like I am a guest in a long tradition of art as service.

Why do you do this work?

I do this work because I believe creativity is a way of being present to life. Drawing, writing, and teaching are how I honour being alive and how I stay awake to the shimmer in ordinary things. After everything I’ve lived through, the loss of my first child, illness, and long seasons of uncertainty, my creative practice has been both refuge and revelation. It gave me a way to keep going, to make beauty out of difficulty, and to offer something back. What keeps me devoted is the reciprocity because when I teach or share my work, I see how creativity opens something in others too. That exchange of attention, tenderness, and presence feels to me like the truest reason for doing anything at all.

What is the positive impact you hope your work will have?

I hope that my work helps people slow down and notice the beauty that’s right in front of them, like the shimmer of light on a leaf, the way every single leaf on a tree is unique, the quiet miracle of ordinary daily life. If someone feels less alone because of something I’ve written, or if they discover a creative practice that brings them calm and joy, then I feel I’ve done my work. What matters most to me is that my work offers companionship and fosters reciprocity, that it reminds us to give back more tenderness, attention, and care than we take from the world.

What do you value most about what you do?

What I value most is the connection my work creates, both for myself with the natural world around me, and with other people, my students especially. Drawing and writing help me notice beauty in ordinary things, and sharing that often sparks recognition in others. That sense of companionship and reciprocity is what I treasure most. I am in awe of my international community of students, most of whom have been with me for almost nine years now, and it has been amazing watching them blossom in their creatives lives, and form close bonds with one another, even though they might be continents apart. So beautiful!

If you could communicate one essential thing about your area of expertise to people who don't know about it, what would that be?

If I could share one essential thing, it would be that drawing, painting and writing aren’t really about talent or perfection, but they’re about learning to see. When we give our attention to the ordinary world, whether with a pencil, a brush, or a few lines of words, we discover beauty, meaning, and even comfort we might otherwise miss. Creative practice isn’t about making masterpieces, it’s about being present, and in that presence, finding ourselves more deeply alive.

Is there a particular place in nature, a sight, a building, a book, a work of art, an experience, that you’d like to encourage Companions and others who care about the world, to experience for themselves?

One thing I would encourage people to experience is a simple path outdoors at dawn, when the light is just beginning to filter through the trees. You don’t have to travel far or seek out the grand or famous. What matters is the quiet, the shift of light, the sense that the world is waking. For me, those moments are as profound as any museum or monument. They teach us how to see, how to listen, and how to remember that beauty and renewal are always close at hand.

Two books I often encourage people to experience are Patti Smith’s Just Kids and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. Just Kids is, to me, one of the most profound love stories ever written. It is an exploration of unconditional love, art, and companionship that continues to shape how I think about devotion. And Braiding Sweetgrass is a book of deep reciprocity, reminding us that the natural world is alive with gifts and that our role is to give back in kind. Both books ask us to live more tenderly and attentively, and both have been essential companions on my own path.

What do you think art, craft, design and rural and environmental education can be used to make the world a better place?

I believe they can help make the world better by teaching us to slow down, to notice, to understand reality, and to care. When we learn to make something with our hands, or to draw what we see, or to tend to a piece of land, we begin to understand reciprocity—that we are in relationship with the world, not separate from it. These practices cultivate humility, attentiveness, and compassion. They remind us that beauty is not a luxury, but a way of honouring life itself. If more people carried that kind of seeing and care into their daily lives, I believe the world would become gentler, more sustainable, and more just.

What concerns you most about the world right now?

What concerns me most about the world right now is the way we are losing our capacity for attention and tenderness, toward each other and toward the natural world. Alongside that, I’m deeply troubled by the loss of truth-telling, and by the deception of political leaders in my own country. I feel like many of my fellow Americans are becoming more dumbed-down by the day. Critical thinking and higher education are in danger here. It feels dangerous when trust is eroded at that level, because without truth there can be no real care or justice. I worry about the violence of indifference, the speed and noise of our culture, and the taking without giving back. Yet I still believe we can turn toward another way, through small, steadfast acts of honesty, reciprocity, and care in our daily lives.

Being a Guild Companion, to me, means standing in a lineage of people devoted to beauty, justice, and truth, to the idea that art and craft are not just personal pursuits, but ways of serving the world. That in itself is an honour. What makes it especially meaningful for me is the immense gratitude I will always feel for Clive Wilmer and Jim Spates. Jim first opened my eyes to a more expansive appreciation of Ruskin, and through him I met Clive, and it was Clive who introduced me to the Guild. Both Jim and Clive’s encouragement have been such a gift. They believed in me and urged me to carry on with my work as an artist in a way that felt utterly authentic. To be welcomed into the Guild as a Companion felt both humbling and deeply sustaining, as if I’ve been given not only a home for my Ruskinian spirit, but a responsibility to keep giving back.

How would you describe the value or purpose of being a Companion to someone considering joining the Guild?

I see it as a chance to belong to a living tradition, one that holds beauty, truth, and justice at its heart. It isn’t just about being part of an organisation, but about joining a community of people who believe that good work can make the world gentler and more just. For me, it has meant companionship, encouragement, and a sense that my own work is part of something larger than myself. And I believe that when we truly learn to see—whether through drawing, walking in nature, or paying close attention—we also foster a deeper care for the environment and the earth that sustains us, and the Guild is so beautifully involved in fostering a deeper care for our Earth. To anyone considering joining, I would say: if you long for a place where your creativity, your concern for the environment and the world, and your desire to share beauty can be nurtured, the Guild offers exactly that.

I would love to see the Guild and its Companions bringing the timeless insights of Ruskin to a wider audience, sharing them in ways that feel alive and relevant to our daily lives. The heart of his teaching is as urgent now as it was in the 1800s, but many people today find his Victorian language difficult to approach. I think one of the most valuable things we can do is to carry the essence of his ideas forward in a modern context by translating them, so to speak, so that more people can recognise how profoundly they address the challenges of our own time.

I would love to come to England and participate in an event, showing people hands on the benefits of learning to see by drawing the natural world…can you imagine a retreat at Brantwood? I can. :)

Is there a particular line, or work, or idea, or artistic work of Ruskin’s that resonates for you?

Of Ruskin’s work, The Elements of Drawing has been deeply important to me. It was the book that first opened the door to my own path as an artist, and I still return to its lessons on seeing with reverence. Perhaps even more profoundly, I was taken by Unto This Last. The radical compassion at its heart, the insistence that justice, beauty, and dignity belong in every corner of society, feels like it matters more than ever. The idea that valuing people and the world not for their utility but for their inherent worth has shaped both my art and my teaching, my politics, and my way of being in the world.

Lefteris Heretakis

Ruskin’s Timeless Call: A Conversation with Guild Companion Lefteris Heretakis on Art, Design, and Education

In an era captivated by fleeting trends and hollow profits, the voice of John Ruskin, the 19th-century artist, writer, and social critic, resonates with striking clarity. His words, steeped in a reverence for truth, beauty, and justice, offer a compass for navigating our fragmented world. I recently spoke with Companion Lefteris Heretakis, a designer, educator, and podcaster based in Valencia, Spain, whose 30 year career in visual communication design and higher education has been profoundly shaped by Ruskin’s teachings. Drawing on The Elements of Drawing and The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Lefteris shared a vision for revitalising art and design education, urging us to heed Ruskin’s call: “There is no wealth but life.” Our conversation revealed how Ruskin’s principles can guide us towards a future rooted in ethical imagination and quiet, meaningful action.

From Violin to Vision: A Practitioner’s Path

Lefteris’s journey began not with a paintbrush but a violin. Trained rigorously from childhood, he practised six to seven hours daily, only to realise at 16 that this path was not his own. This led him to art and design, starting with a foundation course at the Kent Institute of Art and Design in 1994, where students were treated as serious creatives with access to inspiring facilities. He went on to study illustration at Kingston University and earned a master’s in Visual Communication at the Royal College of Art. By 2009, he was teaching, driven to give back through dialogue with future designers.

It was during this period that Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing and The Seven Lamps of Architecture became his guiding lights. “I was inspired by Ruskin’s words,” he told me, quoting, “What we think, or what we know, or what we believe is, in the end, of little consequence. The only consequence is what we do.”. “These works hold the keys to saving art and design education,” he said with conviction. Ruskin’s emphasis on practice over theory, on the act of creation as an expression of moral purpose, struck a deep chord. “His ideas, written over a century ago, feel as though they were crafted for today’s digital disconnection and commercialised education,” Lefteris noted, echoing Ruskin’s lament: “We have much studied and much perfected, of late, the great civilised invention of the division of labour; only we give it a false name. It is not, truly speaking, the labour that is divided; but the men.”

The Digital Divide and Ruskin’s Craftsmanship

The advent of digital technology in the late 1980s and early 1990s promised to enhance artistic practice but often severed ties with tradition. “When digital arrived, we didn’t know how to integrate it thoughtfully,” Lefteris explained. “There was no need to abandon tradition; we could have used digital tools to continue it beautifully.” Instead, an obsession with appearances—polished surfaces over substance—took hold, a trend Ruskin would have deplored. As he wrote in The Seven Lamps of Architecture, “The highest reward for a person’s toil is not what they get for it, but what they become by it.” This focus on becoming, on the sacred essence of craftsmanship, is what Lefteris believes we must reclaim.

In academia, the integration of art and design into universities has further skewed priorities. The push for theoretical dissertations, while valuable, has diminished practice. “We have 25% theory, which is splendid and important, but 75% practice—that’s what’s been forgotten,” Lefteris said. “Those who focus solely on research, without practising, are leading the field astray.” Ruskin’s insistence on doing, on aligning hand, heart, and eye, offers a corrective. His Elements of Drawing emphasises “attentive seeing,” urging creators to observe with care and intention, a practice that counters the superficiality of our digital age.

The Commercialisation of Education: A Ruskinian Critique

The commercialisation of education, Lefteris argued, is a modern betrayal of Ruskin’s vision. In the UK, universities outsource services like security and catering, inflating costs while reducing teaching staff. “This is a plague,” he said bluntly. “Students are treated as clients, expecting ‘value for money,’ which distorts the honest exchange education should be.” He recounted a disheartening experience at a UK university, where a vice-chancellor’s failed project disrupted teaching with construction noise, leaving students feeling neglected. “If students feel nobody cares, they’re not engaged,” he said, echoing Ruskin’s warning in Unto This Last: “The first of all English games is making money… But it is a bad game, and a worse education.”

In contrast, countries with free education, such as some in Europe and Asia, often provide better resources, though public institutions may suffer from outdated curricula. The best teachers often gravitate to private schools for better pay and flexibility, meaning “the best teachers rarely meet the best students.” Ruskin’s focus on practice and ethical purpose could bridge this gap, prioritising students over profit.

Awakening the Moral Imagination

For Lefteris, the heart of design education lies in what Ruskin called “hand-heart-eye coordination”—aligning actions, emotions, and ideas. “Ruskin wrote that art, craft, and design, rightly taught, awaken the moral imagination, guiding the hand and heart towards truth, beauty, and justice,” he said. This is not just about creating objects but designing lives. He shared the story of a Leeds student, trained in graphic design, who applied its principles to build a successful pub business. “Teaching design isn’t just about making things,” Lefteris said. “It’s a way of thinking, helping students design their lives within moral and ethical boundaries.”

When a student experiences this awakening, “there’s an energy in the room,” he noted. Ruskin’s teachings urge us to ask, “Why are we making this? For whom? What does it uphold?” These questions transform the classroom into a space for ethical imagination, not mere visual production. As Ruskin wrote, “True craftsmanship is an act of love.” Designers must care deeply, infusing their work with purpose, not chasing wealth or self-gratification.

The Guild of St. George: A Call to Quiet Action

As a companion of the Guild of St. George, Lefteris is part of a global community across 12 countries, united by Ruskin’s vision of living as though the world were sacred, restoring harmony between humanity, nature, and the divine through quiet, meaningful action. “In a world driven by individualism and profit, these ideas can feel out of place,” he admitted. “You can’t go around saying this stuff—people might sideline you, especially when you mention the divine in a startup-obsessed culture.” Yet Ruskin’s call to align values with actions is universal, transcending time and culture.

The Guild offers a space to connect with others who share this commitment. For those hesitant to join because they’re not “Ruskin scholars,” Lefteris was clear: “Ruskin wasn’t a scholar; he was a practitioner.” The invitation is to live differently—thoughtfully, simply, with care for the world. “We need more guilds,” he said, “groups of people working to make life better through quiet action.”

Ruskin’s Warning and Today’s Challenges

Ruskin’s words capture the crisis of our time: “We’ve mistaken wealth for virtue and progress for wisdom. We build great engines in monster cities, yet forget that our soul is starving.” In the West, individualism has eclipsed collective responsibility. “It’s all me, me, me,” Lefteris said. “We need to realise we’re one humanity.” In Asia, he’s seen cultures that retain values of respect and community lost in the West. In the UK, we’re sliding towards what Ruskin called “illth”—the opposite of true wealth, driven by greed and selfishness. “Everyone’s a mini-tyrant in their workplace or family,” he observed.

The solution lies not in blaming politicians—“they’re powerless,” Lefteris said—but in our collective actions. We must act reflexively, applying Ruskin’s lessons, reflecting, and refining. “I find clarity in the pre-dawn hours, when nature is still, and there’s a beautiful silence,” he shared. The Guild could offer spaces for such reflection, perhaps through “pre-dawn forest bathing” at Ruskin Land, to help us reconnect with our values. We should also learn from global practices. “Europe often ignores what’s happening in the East and West,” he noted. In Asia, small, ethical projects receive support, unlike in the West, where funds are misdirected. The Guild could foster public-private partnerships to prioritise students over profit.

A Vision for Renewal

Lefteris’s work—spanning graphic design, education, and his podcast Design Education Talks—is at the service of the Guild. “Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing and The Seven Lamps of Architecture are an ecosystem for renewal,” he said, “shifting our focus from output to process.” They urge us to design curricula rooted in “attentive seeing” and ethical inquiry. “The design classroom should be a space for ethical imagination, not just visual production,” he added.

Through The New Art School and the Design Education Forum, Lefteris is nurturing future designers and connecting global specialists to revive Ruskin’s principles. His vision is collaboration—through workshops, events, or shared projects—to amplify Ruskin’s ideas. “Let’s learn from East and West to rebuild a world where beauty stems from ethics,” he urged. As Ruskin said, “There is no wealth but life.” The Guild invites us to live with purpose, aligning hand, heart, and eye.

A Call to Companions and Beyond

Ruskin’s frustration was that too few embraced his ideas. Today, we must heed his call to action. The Guild of St. George invites us to live thoughtfully, to design lives and communities rooted in truth, beauty, and justice. For those considering joining, it’s not about scholarship but practice. Let’s collaborate to create ripples of change, transforming education, design, and society for the better. As Ruskin wrote, “The work of our hands and hearts, however small, can restore the broken harmony between man, nature, and God.”

Lefteris Heretakis is a designer, educator, and podcaster with international experience, having worked with multinational corporations, cultural organisations, and start-ups. As an educator, he has taught visual communication challenges in various countries, including the UK, Spain, China, Turkey, Vietnam, and Latvia, emphasising both traditional and digital skills to prepare students for today's rapidly evolving design landscape. Lefteris founded The New Art School to nurture future designers through a curriculum focusing on observation and hand-eye coordination. He also established the Design Education Forum to connect global specialists in art and design education. Additionally, as a podcaster, he hosts and produces "Design Education Talks" and mentors designers worldwide, promoting accessible, expert mentorship. A companion of the Guild of St. George, he is passionate about reviving Ruskin’s principles in art and design education. Connect with him through the Guild or his podcast on design education.

You can find more on his work in links below: