Ewan Anderson: Trees and Rural Geography

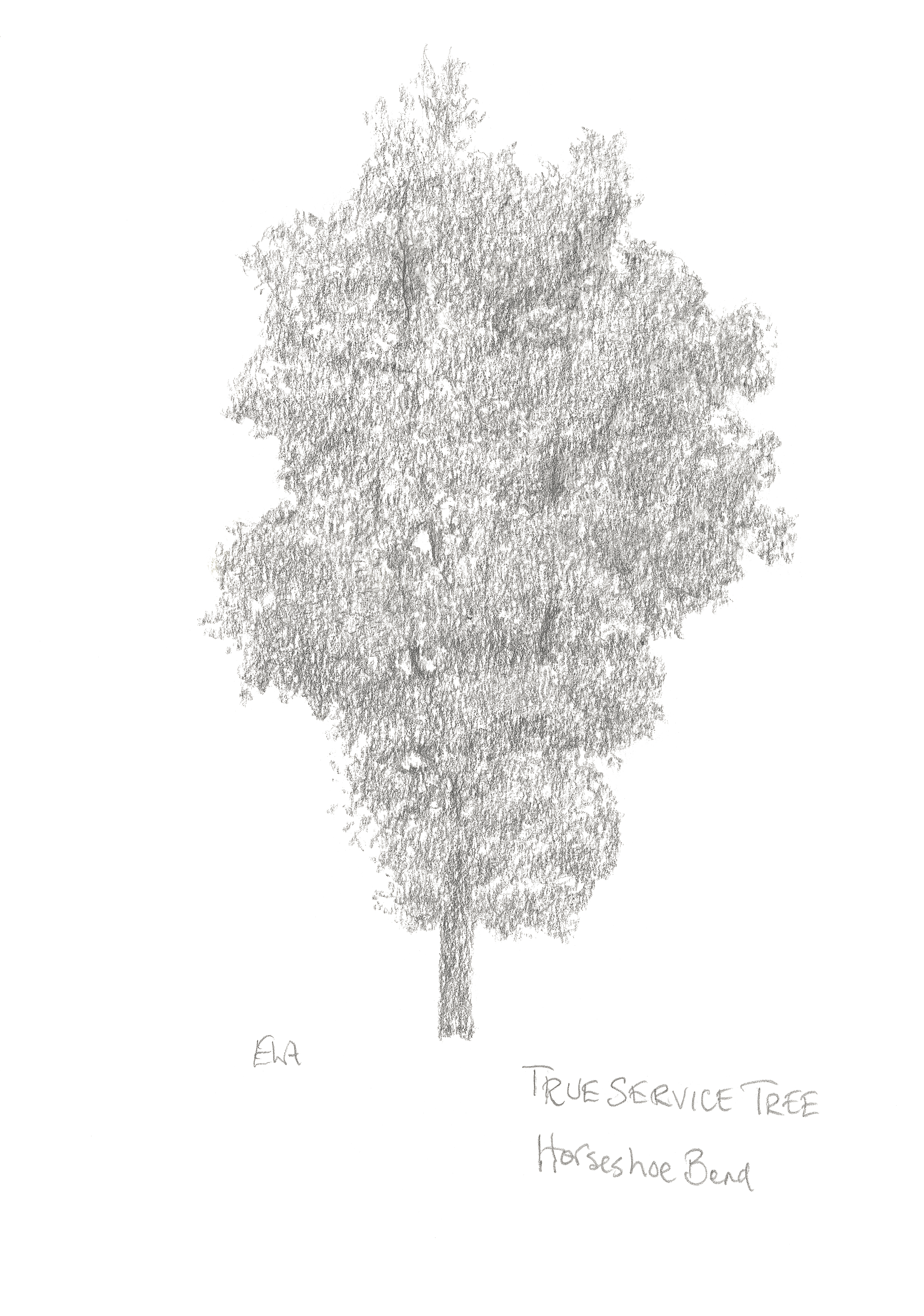

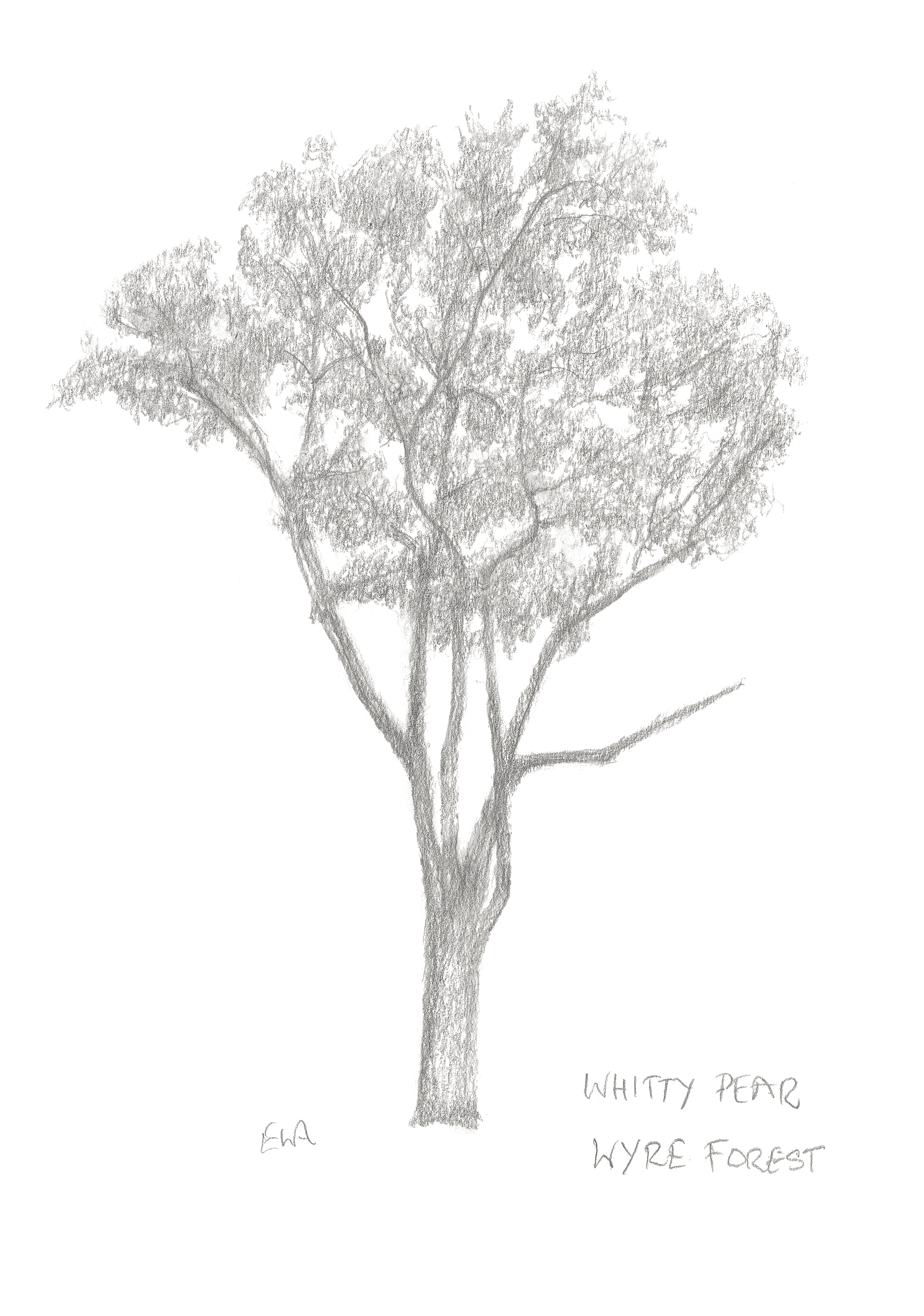

Companion Prof Ewan Anderson recently wrote this for the Rural Geography Research Group's newsletter, and they have kindly agreed that it may be reproduced here, with six of Ewan's drawings of True Service Trees.

Following a career in geography which wandered from schools to colleges and universities and meandered from geomorphology to social and economic geography and finally geopolitics, on retirement it has been a particular pleasure to return to my first main interest, nature especially trees. With the exception of certain fungi, they are the oldest and largest living organisms in the landscape and, as research is gradually revealing, their lives are multifaceted and fascinating. They are, therefore, a key component in plant and rural geography.

Trees are unique in the degree in which they both manifest and combine the aesthetic, the utilitarian and the spiritual. Indeed, William Gilpin (1724-1804), artist ,cleric and originator of the concept of the picturesque wrote: '..it is no exaggerated praise to call a tree the grandest and most beautiful production of all the earth'. Trees are the only element of creation described in Genesis (2:9) as 'pleasant to the sight'.

The aesthetic value of trees has been apparent throughout the history of art. However. it was in the seventeenth century that Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) focused particular attention with his beautiful depictions of trees as dominant features of the landscape.

There followed the landscape movement, inspired by such painters as Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) and John Constable (1776-1837) in whose paintings the tree species can be identified. They were succeeded by, to my mind, the greatest of all tree artists, Ivan Shishkin (1832-1898), on whose huge canvases the majestic trees of the northern forests preside. Tree art continues to flourish to the present day with the work of many artists including one dedicated group known as the Arborealists.

The landscape movement changed the landscape itself using, predominantly, carefully positioned trees to create what is still regarded as one of the supreme art forms of England. William Kent, 'Capability' Brown and Humphrey Repton were among the landscape architects who produced rural settings and vistas acknowledged as masterpieces today.

The utilitarian is relatively obvious. For millennia wood was the ultimate sustainable resource on which human society depended. Trees are replaced naturally and provide fuel, food, building materials, shelter ,medicines and spiritual solace. Possibly this woodland culture helps explain the obvious love of trees that still persists and is demonstrated when trees are threatened, as in the case of street trees of Sheffield and, recently the projected route of the HS2 railway. However, the greatest threat to British woodlands arose from the sixteenth century with the insatiable demand for wooden ships for the mercantile fleet and the Royal Navy. It is said that Admiral Collingwood always carried a pocket of acorns which he planted in all suitable locations. Later mass plantings meant that the age of the great wooden ships had passed before the trees reached maturity and consequently the landscape of Britain boasts more ancient oaks than that of any other European country. Furthermore, apart from woodland products, trees also offer spiritual solace, protect the environment , modify climate, store carbon, provide homes for numerous species of wildlife and, on death, enrich the soil. In 'The Secret Life of Trees', Colin Tudge argues that trees could stand at the heart of the world's economies and politics as they are at the centre of terrestrial ecology.

Although his focus was on timber, in the first great book on British trees, John Evelyn made clear his awareness of the spirituality of trees and the need for the enlightened transformation of the countryside. 'Sylva: A Discourse of Forest Trees and the Propagation of Timber', the first formal publication of the Royal Society, appeared in 1664 and remains a classic.Evelyn ends the book by considering the sacred grove, the enhancement of spiritual life and Paradise itself. Trees may be perceived as objects of worship in the earliest records of religion among most great cultures. It was under the shade of the Bodhi tree that Buddha received Enlightenment while the Tree of Life remains a potent symbol in Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The study of nature over the centuries, has supported the subject of Natural Theology in its development.

The relationship between human life, nature and spirituality has occupied many writers of note, among them John Ruskin and Henry David Thoreau. Indeed, in the footsteps of Ruskin, there is a small current project in which the construction, from geology to vegetation, of the rural Suffolk landscape in the Benefice of Debenham is being examined in its relationships with human activity and spirituality. The links discerned globally have led to the concept of the Pluriverse, the idea that there is not one universe but many. Australian Aborigines perceive a very different universe from that of the capitalist world inhabitants of Sydney. Among current developments which link human life, the landscape and the spiritual are the introduction of rewilding into the countryside and of permaculture into farming.

Rural geography is not only influenced by these changes but also by scientific revelations about the multifaceted lives of trees. These were examined in detail by Peter Wohlleben in his book: 'The Hidden Life of Trees'(2015) and demonstrated visually in a BBC documentary by Dr.George McGavin: 'Oak Tree: Nature's Greatest Survivor'(October 2017). Indigenous peoples are conscious of the wisdom of trees and there is a growing awareness among scientists that trees are sentient beings. Trees react to temperature change, through their roots and leaves they are sensitive to touch, they can distinguish the spit of different animals, they perceive changes in light and moisture, they are aware of danger and have a variety of safety mechanisms and, perhaps most interesting of all, they communicate with animals and with one another. In his book, 'Entangled Life' (2020), Merlin Sheldrake offers scientific evidence which demonstrates the interconnectedness of trees through their mycorrhizal partners.

Apart from work on the Pluriverse and the Debenham project, my main contribution to rural geography has been in locating and drawing Britain's rarest native tree, the True Service Tree (Sorbus domestica). It entered the British list on the strength of a solitary specimen discovered in Wyre Forest in 1678 and known locally as the 'Whitty Pear'. This tree was burned down in 1842 but not before progeny had been planted in the neighbourhood and further afield, including the Oxford Botanic Garden. In 1913, a mature offspring was planted at the Whitty Pears's ancestral site in Wyre Forest. Remarkably, between 1983 and 1991, two very small, indisputably wild populations of True Service Trees were discovered on cliffs in South Glamorgan. Since then, a small population has been located on the Horseshoe Bend of the Bristol Avon, resulting in the site being listed as an SSSI, and individual trees have been found on the Cornish coast and at the confluence of the Rivers Severn and Wye. Biochemical evidence has shown that all these trees are closely related and quite distinct from cultivated continental trees.

Perhaps, in the Post-Covid world, a new spirit of consideration for the treatment of all things green may prevail. The Constitution of Switzerland already includes ' account is to be taken of the dignity of creation when handling animals, plants and other organisms'.

Find out more about the ROYAL GEOGRAPHY RESEARCH GROUP here.