Kevin Jackson - a tribute

Clive Wilmer and Howard Hull pay tribute to their friend, Companion Kevin Jackson, who died suddenly on May 10th 2021

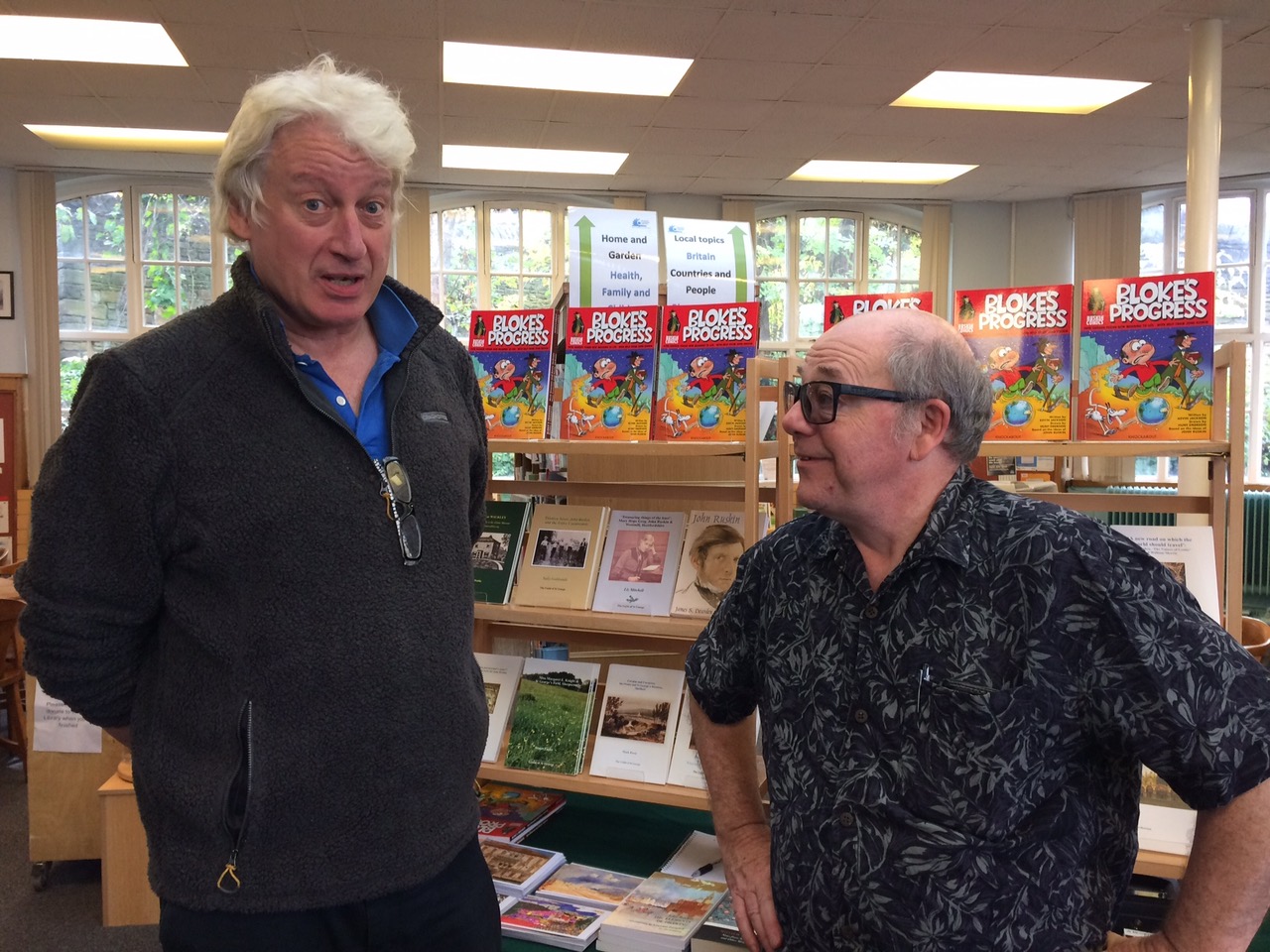

Photograph by Peter Carpenter

Kevin Jackson (1955-2021)

Kevin Jackson (Companion, 2001) died suddenly and unexpectedly on May 10. He was 66.

To his friends – and he had a genius for friendship – Kevin was always The Moose. The nickname went back to his student days and it was easy to see why it had stuck. He was a big man, expansive and genial, with large capacities – for friendship and talk, food and drink, books and films. It sometimes seemed as if, possessing vast resources of knowledge and uncanny powers of recall, he could talk or write about anything.

He made his name as an arts journalist and broadcaster, working for The Independent in its early idealistic days as well as for radio and television – Kaleidoscope, The Saturday Review, Night Waves, Front Row – but by the mid-nineties he had tired of the superficiality that goes with turning out copy and attracting an audience, and so, for not much less than thirty years, he earned a meagre living writing books he never expected would sell in high numbers. The range of his subject matter is stunning: the language of cinema, great voyages, Lawrence of Arabia, vampires, Egyptian archaeology and, of course, the natural and cultural history of the moose. Among those that have meant most to me I’d like to name two: Humphrey Jennings (2004), the biography of another polymath, best-known as the visionary maker of documentary films about London during the war, and Constellation of Genius (2012), an alphabetical survey of 1922, the year in which Modernism took off.

And of course, there was another polymath he wrote about. The Worlds of John Ruskin (2009) is that improbable thing, a brief account of our first Master’s complex life and achievement. Increasingly, this is the book one recommends to new readers of Ruskin. It is not only short, but lively, lucid and readable. It is also, thanks to collaboration with Stephen Wildman, then Director of the Ruskin Library at Lancaster, wonderfully well illustrated.

The Worlds of John Ruskin was not Kevin’s only approach to the arch-polymath. Quite as important were the Ruskin comics, collected together as Bloke’s Progress (2018), to which Howard Hull pays tribute elsewhere in this newsletter, and it is also worth reminding Companions of another A-Z – this one for your coat pocket – A Ruskin Alphabet (2000), which will tell you about everything from Art to Zoology, to say nothing of Etymology and Pubic hair.

I have tried to sum up a man who included multitudes. He has, as I should have known, eluded me. I already miss him more than I could have imagined. I also feel that, of course, he must be somewhere here among us still. As someone said on hearing of his death, ‘He was a life force.’

Clive Wilmer

Kevin Jackson was a force of nature, a man with a huge heart, full of joy in life and kindness to others. He was deep thinking, endlessly inquisitive and laughed with the power of an army of souls. It made complete sense that when I talked to him about translating Ruskin's ideas into something like an adventure in a series of cartoons he immediately seized the idea and invented the concept of a Ruskin comic book, 'Bloke's Progress'. Kevin knew exactly how to bring Ruskin into the present by partnering him with a modern-day everyman, Darren Bloke. He also knew the comic genius we needed on board, Hunt Emerson. And so an amazing partnership was born. Kevin and Hunt, powering through Ruskin's ideas, far from dumbing them down, made glorious sunshine out of them. Kevin was a joy to work with for as long as my liver could stand the pace. For him working with others was always something to celebrate. He never once balked at having an idea questioned. If we reached an impasse in tackling a particular idea he would turn full circle and come at it from a completely different direction, always better. Throughout, Kevin gave of his time and affection for us and for what we were trying to do, freely. He was a good friend who lit up the times we worked together and whenever he re-appeared, red wine and new project in hand. The Ruskin world owes him a tremendous debt. Pick up a copy of 'Bloke's Progress' and share in his energy, humour and humanity.

Howard Hull

Clive Wilmer also wrote Kevin's obituary for The Times. He has asked that we share his full draft, rather than the much-cut version that appeared in the paper.

Kevin Jackson (1955-2021)

Kevin Jackson’s short book Moose (2009) is about a species and its significance for human culture and society. Full of insight, wit and out-of-the-way learning, it is also beneath the surface oddly personal. For Moose was Jackson’s nickname, which, earned early in life, stayed with him to the end. He was a big man, handsome and verbally fluent, with a mighty laugh and huge capacities, slightly out of scale with his surroundings, like a friendly beast that has wandered into the room or the conversation. It went with the energy and generosity that many of his friends have remarked upon since his death: ‘I thought he was indestructible,’ said one. ‘He was an Ode to Joy,’ wrote another.

Not many people have been members of both the Guild of St George (the earnest charity founded by John Ruskin) and the London Institute of Pataphysics (a zany society of latter-day French surrealists), but the Moose was. In much the same way, the variety of the topics he wrote about seemed infinite. He consumed books voraciously, ingested quantities of learning and language at great speed and went from one project to another with unfailing energy. It was always delightful to be with him when he held forth. His learning was lightly worn, his tastes were wide and generous, and he was blessed with a vivid sense of humour.

Kevin Jackson, as he often reminded you in the local accent, was ‘transpontine’ – a South Londoner. He was born in Tooting in 1955. Alec Jackson, his adored father, was a Colonel in the Life Guards and Riding Master of the Household Cavalry. His mother was Alma Dorothy Louise Jackson (née Rolfe). He studied at Emanuel School in Wandsworth (1966-73) and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he took a First in English in 1977. He then embarked on an abortive PhD and ended up at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, where he taught and studied from 1980 to 1982. The thesis was to have been about the annus mirabilis of Modernist literature, 1922, a subject which was to provide, much later on, an outstanding book, Constellation of Genius (2012). He did eventually earn a Cambridge PhD in recognition of his publications.

Returning from Nashville, Jackson trained as a producer for the BBC and soon began producing arts programmes, first for Radio 4, then BBC 2. In 1987 he joined the staff of The Independent, then the great hope of quality journalism, where he soon became Associate Arts Editor. Jackson was a wonderful journalist, discovering new voices and championing neglected gems. but in 1993 this ceased to be the main source of income. Instead, he dedicated his life to writing books; occasionally potboilers but, more often than not, vehicles for his grand passions.

At a dinner party in Oxford in 1990, he met and fell in love with the American literary scholar Claire Preston, who soon afterwards became a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, where the pair married in 2004. They moved into a house they christened ‘Moosebank’ in the village of Linton near the source of the Cam.

Within the range of Jackson’s work, it is probably his books on cinema that are best known. His knowledge of the medium was vast. There is an A-Z called The Language of Cinema (1998). There is Schrader on Schrader (1990), his book-length interview with the director and screenwriter who wrote Taxi Driver. There are three British Film Institute monographs on films that were points of reference in his conversation: Lawrence of Arabia (2007), Withnail and I (2008) and Nosferatu (2013). Above all, there is Humphrey Jennings (2004), his luminous biography of the maker of such great war-time documentaries as Diary for Timothy. This is a major work of cultural history.

Jennings – poet, painter, social analyst and surrealist innovator as well as director – was one of Jackson’s tutelary heroes. Others include Coleridge, Ruskin, André Breton, Anthony Burgess and Iain Sinclair – all intensely productive, polymathic enthusiasts spurred on by some vision of a better world. Jackson never seems to have quite believed he belonged in their company – though in Sinclair’s London Orbital (2004), a voyage of discovery around the M25, he emerges as a hero in his own right.

Jackson was a humanist of the old school, though one enamoured of David Bowie and the pop trio ‘I, Ludicrous’. His best books offer what the student or general reader needs, but few nowadays provide. Many Victorianists, for instance, will tell you that The Worlds of John Ruskin (2009) is the best short introduction there is to its subject’s complex life. It is typical of Jackson that he also wrote the text for a series of comics by the graphic artist Hunt Emerson, in which a latter-day everyman, Darren Bloke, encounters the spirit of Ruskin and is stunned to find how relevant he is. The comics are collected in Bloke’s Progress (2019).

Some of Jackson’s most recent work features on audiobooks – a series on famous voyages, for example – and he made a series of films out of his life-long obsession with the occult and the lore of vampires. The audiobook Legion is his study of the most complex of his heroes, T.E. Lawrence, a man of action with the soul of a poet. He was not the only fascinating figure to haunt Jackson’s capacious imagination. For Jackson was multitudes: poet, translator, voyager, bon viveur, scholar, true companion, moose lookalike. We shall miss all of him.

Kevin Jackson PhD, FRSA, writer, broadcaster and filmmaker, was born on January 3, 1955. He died on May 10, 2021, aged 66.

Kevin with Hunt Emerson at a comic book workshop in Sheffield in 2019.