Venice celebrates her adopted son in his bicentenary year. Master of the Guild Clive Wilmer reflects on the occasion.

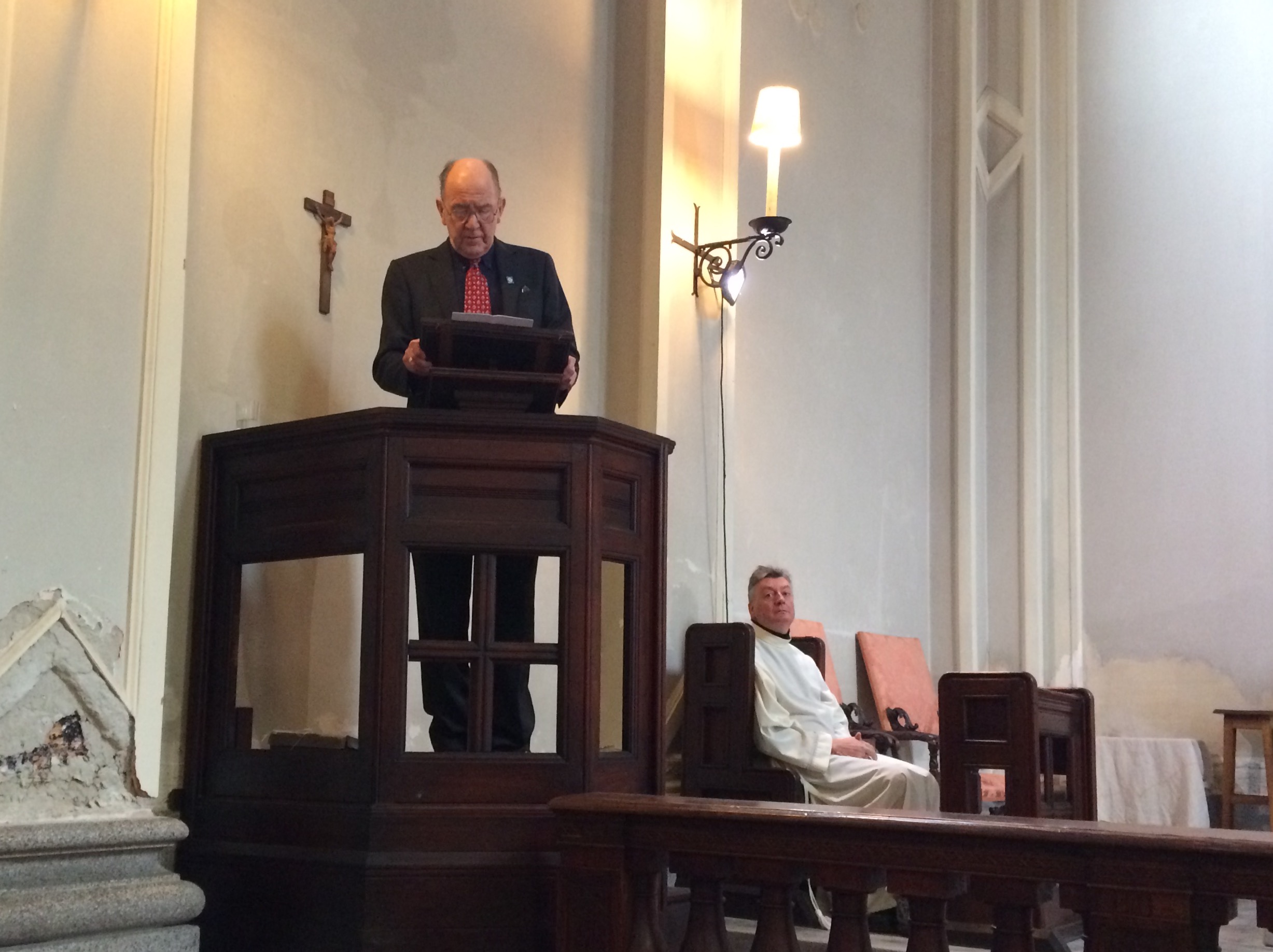

Not long ago the Guild was asked to participate in a Venetian tribute to Ruskin on his 200th birthday. The Warden of the Scuola San Rocco, Franco Posocco, who has recently become a Companion of the Guild, told me that he and his colleagues wanted to give thanks, as Venetians, for Ruskin’s work. The plan was to place a wreath on the memorial to Ruskin on the outside wall of the Pensione La Calcina, where he is said to have stayed in the 1870s. Franco wondered if we could precede the wreath-hanging with a service in Ruskin’s honour at St George’s Anglican Church. When the Chaplain, Malcolm Bradshaw, agreed to this proposal, I was asked to put together a service based on Matins, the traditional morning service well known to Ruskin. I was also asked to give a short address.

The Board of Directors decided to support this initiative by funding my visit and sending three other Guild representatives: one Director (Howard Hull), one Guild employee (Ruth Nutter) and one younger Companion, who would be awarded a small bursary to make the visit possible. In the event, this was won by Malaika Cunningham, who has been very active in our Sheffield project. Read her reflections here.

To my feeling, the occasion could not have been better. The weather was awful, it must be said, with two days of rain and flooding. But we survived through community spirit! On the Saturday we walked around Venice, visiting in particular the Scuola San Rocco with its sixty-two Tintorettos and the Scuola di San Giorgio, where the Carpaccio painting of St George and the Dragon hangs. Both institutions were important to Ruskin in his conception of the Guild,

The Sunday morning was extraordinary. The church was packed to the rafters – there were at least 80 people there, probably more. About a third of them were Italian, mostly but not all from the Scuola San Rocco, and I was glad I had asked my friends Geraldine Ludbrook and Companion Emma Sdegno to provide an Italian translation of the service. The English speakers were members of the usual congregation, overlapping with supporters of the city’s Circolo Italo-Britannico and people from Ca’ Foscari University. Just a few were passing visitors from places as far afield as Singapore and New England. There were two very Ruskinian readings from the Bible. Genesis 28 (Jacob’s ladder) was read in English by the churchwarden, David Newbold; the other, the Parable of the Vineyard (Matthew 20) was read in Italian by Emma, representing both the Scuola and the Guild. The service was from the 1660 Book of Common Prayer, and there were hymns by George Herbert, St Francis of Assisi and the co-founder of the National Trust, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, Rawnsley’s hymn was originally written for Ruskin;’ funeral at Coniston Church in 1900. The service was followed by short speeches from the Deputy Mayor of Venice and Franco Posocco. The subsequent wreath-hanging, stimulated by a superb Prosecco, was wonderfully international and convivial.

My address touched on the two readings with particular reference to the lecture ‘Traffic’ and Unto this Last. The text is below.

Clive Wilmer, Master of the Guild

St George’s Church, Venice 3.ii.19

A Service to mark the Bicentenary of the birth of John Ruskin (1819-1900)

Address

“And Jacob awaked out of his sleep, and he said: ‘Surely the Lord is in this place; and I knew it not… How dreadful is this place! this is none other but the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.’ And Jacob vowed a vow, saying, ‘If God will be with me, and will keep me in this way that I go…, then shall the Lord be my God: and this stone, which I have set for a pillar, shall be God’s house.’”

Verses from Genesis 28

This is the passage in which the patriarch Jacob realises that he has been chosen by God to be the founder of a nation. He responds with appropriate solemnity: he makes a vow that he will build a temple – to circumscribe the site of his covenant with God, declaring it to be sacred.

This is a myth of origin. First, it gives expression to the sacred calling of Israel – ‘Israel’, you will remember, is to be Jacob’s name – and, secondly, it explains the significance of temples in the Jewish religion and, by extension, of churches in Christianity. In doing so, it also brings an aura of sanctity to one of the primary human arts: that of architecture. Jacob takes the stone he has just used as a pillow and turns it into a pillar – pillow to pillar in English is a nicely fortuitous pun – and, in doing so, he exemplifies the work of the builder or architect. To put it another way, he takes nature and turns it into art.

Today we give thanks for the work a man of extraordinary genius who spent his life reflecting on that relationship, nature to art, and on the meanings communicated through buildings. John Ruskin, who devoted much creative energy to praising, describing, measuring, drawing and, in the end, saving the buildings of Venice was born two hundred years ago this week. Ruskin is sometimes said to be the greatest writer on art in the English language, but it is important to notice that, for him, art was not everything. Indeed, to be paradoxical, art was only important when it recognised that there was something more important; and that something was Nature – made by God, Ruskin thought, for the pleasure, nourishment and instruction of human beings. ‘All great art,’ he wrote, ‘is the expression of man’s delight in God’s work, not in his own.’ That being the case, he called his great study of Venetian architecture The Stones of Venice, not The Buildings of Venice. For him, there was no human artefact more beautiful than Venice, but even Venice was nothing without the sea, which both nurses and imperils it. Moreover, good works of art draw our attention to nature. Such a building as St Mark’s Basilica is made from natural materials and it displays those materials for our admiration – think of the marble cladding on the facade. It also imitates nature in its decorative imagery and recalls natural spaces in its formal arrangements.

But what of Jacob’s temple – Beth-el, the house of God? In a fiercely eloquent lecture of 1864, Ruskin reflected on the story we have heard this morning. The lecture was given in the Yorkshire town of Bradford and, for the benefit of his local audience, he wonderfully imagined Jacob as a boy, not in the Holy Land but on the Yorkshire moors, forced to lie down for the night on the slopes of a hill called Whernside. Exactly as Jacob does, he dreams of angels and wakes to say: ‘How dreadful is this place; surely this is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.’ And Ruskin comments:

'This PLACE, observe; not this church; not this city; not this stone, even, which he puts up for a memorial – the piece of flint on which his head was lain. But this place; this windy slope of Wharnside [sic]; this moorland hollow, torrent-bitten, snow blighted! this any place where God lets down the ladder.'

It was customary in the nineteenth century to inscribe Jacob’s words over the gates of churches: ‘This is the house of God…’ But this, Ruskin tells his audience, is not the right interpretation. Whenever we are moved by the beauty or power of nature, God has let down the ladder to us. The truly sacred place is not the church, not Jacob’s promised temple, not an artefact, but nature; and not nature as a large abstraction, but the particular piece of it in which you find yourself – Jacob’s wilderness, the Yorkshire moors, the sea breaking on the Zattere. [You may feel], Ruskin tells his Bradford audience, ‘as if I were trying to take away the honour of your churches. Not so; I am trying to prove to you the honour of your houses and your hills; not that the Church is not sacred – but that the whole Earth is.’

So Ruskin reaches into matters that profoundly stir us today. Elsewhere he writes:

'God has lent us the earth for our life; it is a great entail. It belongs as much to those who are to come after us, and whose names are already written in the book of creation, as to us; and we have no right, by anything that we do or neglect, to involve them in unnecessary penalties, or deprive them of benefits which it was in our power to bequeath.'

How have we treated the earth, we to whom God entrusted it? Can we be proud of our stewardship? This is the man who by the end of his life had come to believe that human activity was already – in 1884 – fatally damaging the climate of our planet.

Moreover, in Ruskin’s understanding of the world, everything is related to everything else. It is what makes his writing so rich and various. In his autobiography he reflects on how his temperament as a boy belonged to the spirit of his time, particularly in his Romantic love of nature. Before (say) a hundred years ago, he says in his autobiography – I am partly paraphrasing -- ‘no child could have been born to care for mountains, or for the men that lived among them, in that way. … there had been no “sentimental” love of nature’, nor had there been that caring modern love for “‘all sorts and conditions of men,” not in the soul merely, but in the flesh.’ The quoted phrase comes from one version of the very service you are now attending, Matins: it is from the title of a prayer ‘for all sorts and conditions of men’. In Ruskin’s case it meant that despite his very great wealth, he cared about the condition of the poor in the new industrial cities, those ‘sent like fuel to feed the factory smoke’ (as he put it) and condemned to the squalor of the slums. Again and again in his later writing Ruskin cries out that he can no longer see the mountains and flowers, the pictures and churches that give him pleasure, because his sight and consciousness are wholly focused on the misery of the poor.

Just as those pleasures are to be understood as evidences of God’s love for humanity, the sufferings of his fellow human beings reminded Ruskin of the commandment that we love on another as God has loved us. In 1860, in the short masterpiece called Unto this Last – the title is taken from the Parable of the Vineyard in St Matthew’s Gospel with its deep message of common human need – Ruskin laid aside his enthusiasm for art and nature and addressed the issue of economic justice. He attacked the fashionable political economists as lackeys of an unjust system, fabricating a pseudo-science to justify greed and callousness:

'I know no previous instance in history of a nation's establishing a systematic disobedience to the first principles of its professed religion. The writings which we (verbally) esteem as divine, not only denounce the love of money as the source of all evil, and as an idolatry abhorred of the Deity, but declare mammon service to be the accurate and irreconcilable opposite of God's service: and, whenever they speak of riches absolute, and poverty absolute, declare woe to the rich, and blessing to the poor.'

It is interesting that, in the period when Ruskin wrote that, he was quite unsure of his own faith. Like many of the troubled intellectuals of his day, he had given up going to church and had stopped believing in an afterlife. Yet the fierceness of inner conviction and deep faith burned through his utterance. Reacting against the literalist Christianity in which he had been schooled, he began to think of the Biblical stories as myth – deeply significant myth, but fiction none the less. Yet, by contrast and perhaps as a consequence, he insisted on a literal understanding of the Bible’s ethical teaching. The Parable of the Talents is about money. The Parable of the Vineyard is about employment. The rich young man asks Jesus: ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’ And the answer comes back: ‘Take all that thou hast and give to the poor.’ Like St Francis, with whom he identified, Ruskin started in middle life to give away his wealth. That is the context in which we are to understand the conclusion to Unto this Last, perhaps the profoundest thing he ever wrote:

'THERE IS NO WEALTH BUT LIFE. Life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration. That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest number of noble and happy human beings; that man is richest who, having perfected the functions of his own life to the utmost, has also the widest helpful influence, both personal, and by means of his possessions, over the lives of others.'

Clive Wilmer